Missouri lawmakers and citizens alike believe the other group should have less power when it comes to initiative petitions.

Both have proposed policies to achieve these aims that could end up on the November 2026 ballot.

Conservatives in the Missouri legislature have for years pushed to change the initiative petition process in order to make it more difficult for citizen-led movements to change statute or the state’s constitution.

Takeaways

- Initiative petitions are a legally recognized process through which citizens can collect signatures to put before voters a question that, if passed, can change the state constitution and state law.

- Missouri has a long history of lawmakers from both parties trying to limit citizens’ initiative petition power when their votes run contrary to lawmakers’ policies.

- Both Missouri lawmakers and citizens have been pushing to restrict the other group’s power when it comes to initiative petitions.

- If a recently launched initiative petition campaign gathers enough signatures, Missouri voters’ 2026 ballots might include questions about restricting both citizens’ and lawmakers’ powers regarding initiative petitions.

And earlier this year — following the partial repeal of paid sick leave provisions put into statute by Proposition A and the approval of a ballot question seeking to overturn abortion access measures put in the constitution by Amendment 3 — a citizen-led movement emerged, aiming to make it more difficult for state lawmakers to overturn or roll back policies that voters have approved.

‘It hamstrings what we can do’

Every year since he was elected to the Missouri House of Representatives, Ed Lewis has sponsored a bill that would change the initiative petition process.

“My freshman year, five years ago, I filed a bill that dealt with initiative petition reform,” said Lewis, a Republican from Moberly. “It included statutory initiative petitions, constitutional initiative petitions, referendums — way more than we were going to accomplish.”

While the target of his bills has narrowed over the years, Lewis said he’s remained an advocate for changing the initiative petition process because “there have been several initiatives that were things that worked against what we want to see happen in our state, especially when it comes to things we are putting in our constitution.”

Those things included legalizing recreational marijuana and expanding access to abortion.

The “recreational marijuana (amendment) put 39 pages of basically an industry’s business model into the constitution — how much they could be taxed, restricting us from being able to say what percent THC they could have, making sure there were no criminal penalties relating to marijuana,” Lewis said. “It really hamstrings what we can do to make our communities safe.”

When Missouri Gov. Mike Kehoe called for an extraordinary session in August so legislators could vote on a new congressional district map, he added initiative petition reform to the list of issues lawmakers were allowed to address.

Back in Jefferson City, Lewis again proposed changes to the initiative petition process. This time, his proposal was met with more enthusiasm, ushered through the legislative process and passed out of both chambers in a week. It doesn’t require the governor’s signature, so it is now in the hands of the secretary of state, who is responsible for putting it on the ballot.

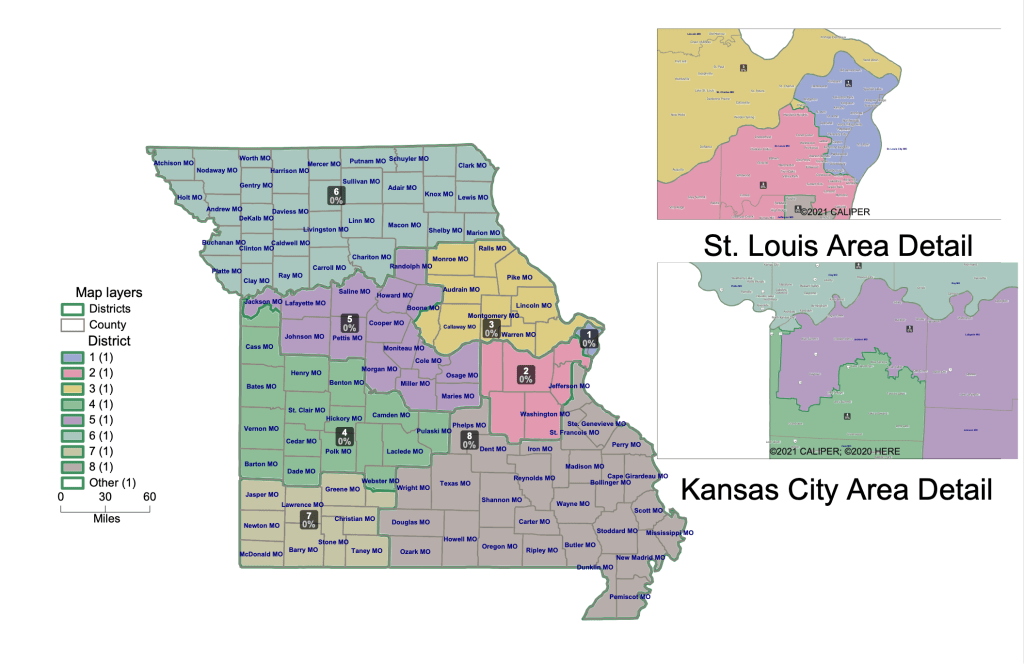

Lewis’ resolution passed at the same time as a new congressional map that may give Republicans a majority in seven of the state’s eight districts.

Under Lewis’ resolution, an initiative petition-based ballot question would need to receive support from a simple majority in all eight of the state’s congressional districts in order to amend the constitution.

It did not change the threshold — a simple majority of the entire state — for voters to approve a ballot question that would change state statute, but it will ask voters to make several other changes, as outlined in the proposed ballot question:

Shall the Missouri Constitution be amended to:

- Stop foreign nationals and foreign adversaries of the United States from providing funding to influence ballot measure elections, and allow criminal prosecution of violators;

- Require public hearings be held to get public comment before initiative petitions are placed on the ballot;

- Require a majority of voters in each congressional district to approve initiative petitions to amend the constitution; and

- Make available to each voter the full text of initiative petitions with their ballot?

Opponents of the resolution argued that several of its provisions are already in state law and were only included as “ballot candy” to incentivize Missourians to approve it.

Lewis countered that his proposals were only partially covered by existing state law.

For instance, voting precincts are already required to make the full text of proposed laws or amendments available to voters. But many hang the text on the wall, which Lewis said is impractical when the recreational marijuana amendment included 39 pages of regulations.

As for the public hearings, Lewis said state law already makes it possible for citizens to submit public comments on initiative petitions. But he believes there should be another forum for people to express “why they are for or against it … so people can hear both sides.”

Senate Bill 152, passed by the Missouri legislature earlier this year, already bans foreign donations to ballot measure campaigns. But Lewis said putting similar measures in the constitution will cement the government’s authority to enforce that law.

“Because the constitution gives us the right to do what we’ve tried to do in statute, some people have brought suit against us to try to have (laws) declared unconstitutional,” he said. “Well, if we put it in our constitution, then it won’t be unconstitutional.”

Seeking consensus

The eight-district requirement is meant to ensure constitutional changes are “something there is truly consensus on,” Lewis said, pointing to recent constitutional amendments that were passed mainly by voters in more populous urban and suburban areas.

Previously, Lewis had sought to require majority approval in five of the eight districts before the constitution could be amended. But he said he received pushback from Democrats who said his proposal would disenfranchise voters in the other three districts.

He said Republicans, on the other hand, were encouraging him to propose a seven-district threshold.

“Seven out of eight would have been patently unfair to liberals and would have been exactly what the conservatives wanted,” he said. “Conservatives wanted me to run seven out of eight, because we could do things in seven of the eight districts, especially with redistricting.”

“I don’t want it to be used for conservatives to change the constitution and I don’t want it to be used for liberals to change the constitution,” he added. “To change the constitution, we should have to agree statewide. There should be a consensus between at least 50% of all across the state to change it.”

Critics of Lewis’ proposal argued that requiring majority approval in every congressional district would be an insurmountable hurdle.

“It’s ridiculous, and we’re never going to see anything passed, realistically,” Rep. David Tyson Smith, a Democrat from Columbia, argued on the House floor. “You’re making things virtually impossible to pass.”

Following Smith’s comments, Lewis listed five successful ballot measures from the past 25 years that would have cleared the eight-district requirement, including the effort to raise the state minimum wage in 2006.

Widely known ballot measures, including Medicaid expansion, recreational marijuana legalization and Amendment 3, did not clear the threshold.

Missouri’s new congressional map

Democrats argued that under Lewis’ proposal and the new congressional map, Republican-leaning districts — as many as seven of the eight — would have greater power to block initiative petitions from passing even if a ballot measure achieves majority support statewide.

Benjamin Singer is the co-founder of the cross-partisan Respect MO Voters coalition, which is working to make it more difficult for lawmakers to repeal or roll back policies passed by voters.

He said one of the “especially shameless” aspects of Lewis’ proposal is that while it increases the threshold for approval of citizen-led measures, it doesn’t change the threshold for amendments put on the ballot by lawmakers.

“They’re establishing a double standard where they’re claiming that they want to make it harder to amend the constitution, but over 80% of constitutional amendments come from the legislature,” Singer said. “They are not raising the threshold for legislatively referred amendments to pass — only for ones coming from the people.”

Lewis said he’s “not against changing that … but it would be different.”

“We’d have to rein ourselves in,” he said. “I’m not sure we could get consensus on that.”

However, he said getting a legislature-based question on the ballot and an initiative petition-based question on the ballot are very different processes.

On the legislative side, he said politicians first have to be elected by a majority of their constituents, then get their resolution through the legislative process — requiring majority approval from committees and both chambers multiple times — before it is sent to the voters.

“The idea that someone gets some signatures collected, puts it on the ballot and then they have to get 50% plus one, to say that’s equal to the threshold and the public scrutiny that we have to go through — those are completely different things,” Lewis said. “Currently, we hold a majority, and it’s a little easier for us to do it.”

“But even with a supermajority, we haven’t been able to get this thing put on the ballot. Even with a supermajority, there are checks and balances in the legislative process,” he added. “One check and balance that we need to provide for constitutional amendments for the initiative petition process is a higher threshold.”

Asked how his proposed changes would be affected by the new congressional map — which may give Republicans seven of the state’s eight seats — Lewis said he thinks “it actually makes it easier to pass constitutional amendments.”

“It actually does make the districts more competitive and makes it more reasonable that you ought to be able to get 50% in each of the congressional districts,” he said. “The only district that should be tough for a liberal IP should be in (District) 8 and for a conservative IP should be in (District) 1. It’s equally difficult for both conservatives and liberals.”

Raising the threshold for lawmakers

After the 2024 election, Singer — also the CEO of Show Me Integrity, a government accountability and transparency advocacy group — and other organizers held a meeting with volunteers.

At the meeting, a volunteer named Toni Easter told Singer: “If you all do a ballot initiative to save the ballot initiative process, I will be there. I will be in the street for that.”

That sentiment was reaffirmed by a survey of Show Me Integrity’s supporters, which found that of a list of possible strategies for improving Missouri’s democracy, the most popular — with 81% support — was “banning the legislature from continuing to attack the citizen initiative process.”

Easter and Singer then worked together to create Respect MO Voters and launched a town hall campaign that toured across the state.

On that tour, “we knew there would be a populist sentiment, but we underestimated how strong that populist sentiment is all across the political spectrum, that regardless of your party or lack thereof, you don’t want politicians overturning the will of the people,” Singer said.

He said that in Missouri, both Democrats and Republicans have a history of targeting the initiative petition process.

“When Democrats were in the majority in the legislature, they didn’t like that Missourians used the initiative process to limit state and local taxes, and so they … tried to pass restrictions and regulations on the citizen initiative process to make it more difficult to use,” Singer said.

“If you want to end gerrymandering, the only way that’s going to happen is through a citizen initiative, and the only way to stop politicians from overturning and gutting citizen initiatives is by passing the Respect MO Voters amendment.”

Benjamin Singer, co-founder of the Respect MO Voters coalition

But Republican Gov. John Ashcroft “vetoed Democrats’ attack on the initiative process, saying that the initiative process is the process by which citizens, who have no influence with their elected representatives, can take issues directly to the people,” he added.

After hearing from Missourians, Respect MO Voters put together an initiative petition that would ask voters:

Shall the Missouri Constitution be amended to:

- Expand the initiative and referendum petition process by making it a fundamental right;

- Allow courts to revise ballot summaries through lawsuits;

- Prohibit the legislature from weakening initiative or referendum powers;

- Prohibit the legislature from changing or repealing laws enacted through the initiative process, or passing laws similar to those rejected by referendum, without approval from at least 80% of both chambers; and

- Preserve existing majority vote and signature requirements for initiative and referendum petitions?

Asked about the 80% threshold, Singer said it was directly informed by conversations with citizens.

“The polling showed that generally, the higher the threshold, the more voters were supportive of it across party lines,” he said.

As for the prohibition on laws that make the initiative petition process “more difficult,” Singer said the provision was meant to protect signature gatherers from “burdensome regulations.”

On Sept. 16, Singer said Respect MO Voters had recently kicked off its signature collection campaign and predicted the group would “have an extraordinary number of signatures from this first week.”

Asked whether he had a more precise prediction, Singer said a conservative guess would be 10,000 signatures.

“We had over 1,200 people come to our 15 launch events across the state last week (to volunteer), and we are hearing reports of volunteers who already have 50 or 100 signatures gathered in their first week,” he said. “The energy right now to stop politicians from attacking the will of the people is higher than it’s ever been.”

In order to get on the November 2026 ballot, Respect MO Voters will need to collect 300,000 signatures by the beginning of May 2026. According to the constitution, those signatures must come from at least 8% of the voters in two-thirds of the state’s eight congressional districts.

However, Singer said the organization is aiming to get all of the signatures it needs before the start of the new year “so we can get them in before the legislature passes any more restrictions on using the ballot initiative process.”

In addition to talking with their communities, the organization’s volunteers are collecting signatures at several upcoming events.

Singer said events in recent years — including the passage of a ballot question, sponsored by Lewis, that seeks to overturn the abortion access measure Amendment 3 — have fueled the enthusiasm of the organization’s volunteers and the people signing the petition.

“What the legislature just did really made the case for us of how brazen they are in trying to strip power away from the citizens of Missouri and put all the power in the hands of the politicians in Jefferson City,” Singer said. “They want to make it harder for voters to hold them accountable and to have a check on government.”

Restricting citizens’ ability to amend the state constitution will also affect future redistricting, he said, because “politicians are not going to voluntarily give up their own power.”

“If you want to end gerrymandering, the only way that’s going to happen is through a citizen initiative, and the only way to stop politicians from overturning and gutting citizen initiatives is by passing the Respect Missouri Voters amendment,” Singer said.

Lewis said he had read Respect MO Voters’ petition and believes its proposals would “hamstring the legislature from being able to do what the legislature is supposed to do.”

“I think their purpose is to make sure that they still have access and a lower bar … so it’s easier for them to distort the constitution,” he said.

What’s next?

Lewis’ proposal will go before voters in November 2026 unless Kehoe orders a special election, which could put the question on the April or August ballot instead. If Respect MO Voters gets the signatures it needs, it will have its question on the November 2026 ballot.