Editor’s note: This story was updated Friday, Sept. 12 to reflect the Missouri Senate’s decision to pass the Missouri FIRST Map.

Throughout Missouri’s history, politicians have used their sway in the state legislature to draw congressional maps that help their party at the ballot box.

“What we’ve seen is, of course, Democrats drew lines that tended to favor Democrats and Republicans drew lines that favored Republicans,” said Peverill Squire, a political science professor at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

But to do so halfway through a census period — as the Missouri Senate did Sept. 12, a few days after the House — is almost unprecedented, he said.

Takeaways

- Missouri Republicans are poised to pass a new congressional map designed to oust Democratic Rep. Emanuel Cleaver from his seat in 2026.

- Missouri has a long history of the party in power drawing districts to favor its members, but a very limited history of drawing districts in the middle of the census cycle.

- The unprecedented nature of the current redistricting effort raises questions about the legality of the move, questions the Missouri Supreme Court may ultimately answer.

The only time Missouri has drawn a congressional map outside of the decennial cycle was in 1965. The year before, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that congressional districts must have roughly equal populations, a decision that forced 17 states, including Missouri, to scrap their old maps and draw new ones.

Beyond that, Squire said that midcycle redistricting “is out of the ordinary for Missouri’s history, and it’s rarely been done elsewhere.”

Besides this year’s redistricting battles, “the most recent example was in Texas in the first decade of the century, and there was a lot of commentary about it being done at that point in time,” Squire said, referring to the Texas legislature’s 2003 redrawing of the state’s congressional map, which the U.S. Supreme Court mostly upheld.

In late August, Missouri Gov. Mike Kehoe called state lawmakers back to Jefferson City to vote on a new congressional map. The decision followed efforts by the Trump administration to pressure state leaders to redraw the state’s districts five years early and give Republicans an advantage in the 2026 midterms.

Kehoe’s decision came after Texas redrew its map under pressure from the president and as Democratic states like California and Illinois gear up for their own redistricting fights.

As of the evening of Sept. 11, the new map has been approved by the Missouri House of Representatives and is expected to be passed by the Missouri Senate soon.

What does the Missouri Constitution say about redistricting?

Rep. Dirk Deaton, a Republican from Seneca, sponsored a bill including the map proposed by Kehoe.

During his testimony and floor speeches, Deaton regularly cited a section of the Missouri Constitution that says that besides redistricting following the census, “such districts may be altered from time to time as public convenience may require.”

However, that section refers to redrawing state legislative districts, not federal ones.

Under the section about congressional redistricting, the Missouri Constitution says that following the census, “the general assembly shall by law divide the state into districts corresponding with the number of representatives to which it is entitled, which districts shall be composed of contiguous territory as compact and as nearly equal in population as may be.”

That section notably lacks any language around midcycle redistricting. But Deaton told a House committee on Sept. 4 that the section he’d been referring to “also speaks to redistricting and so you have to read them in harmony together. Both are true at the same time.”

That’s “a pretty weak” argument, according to Allen Rostron, a constitutional law expert and the associate dean of the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law.

“There are certainly some people who believe … we don’t need judges or other people just making up content that’s not there. Those people tend to be on the conservative side of the political spectrum,” Rostron said. “They want strict construction of the plain language — if the right to privacy isn’t mentioned in the (U.S.) Constitution, then it’s not there.”

“So it’s very ironic that the legislature of Missouri, which I think obviously has a majority of conservative voices, and the sponsor of the legislation, who you would think would generally subscribe to that, are completely throwing that out the window,” he added. “They’re making a very liberal argument about the mode of interpretation of a constitution in order to achieve a conservative objective.”

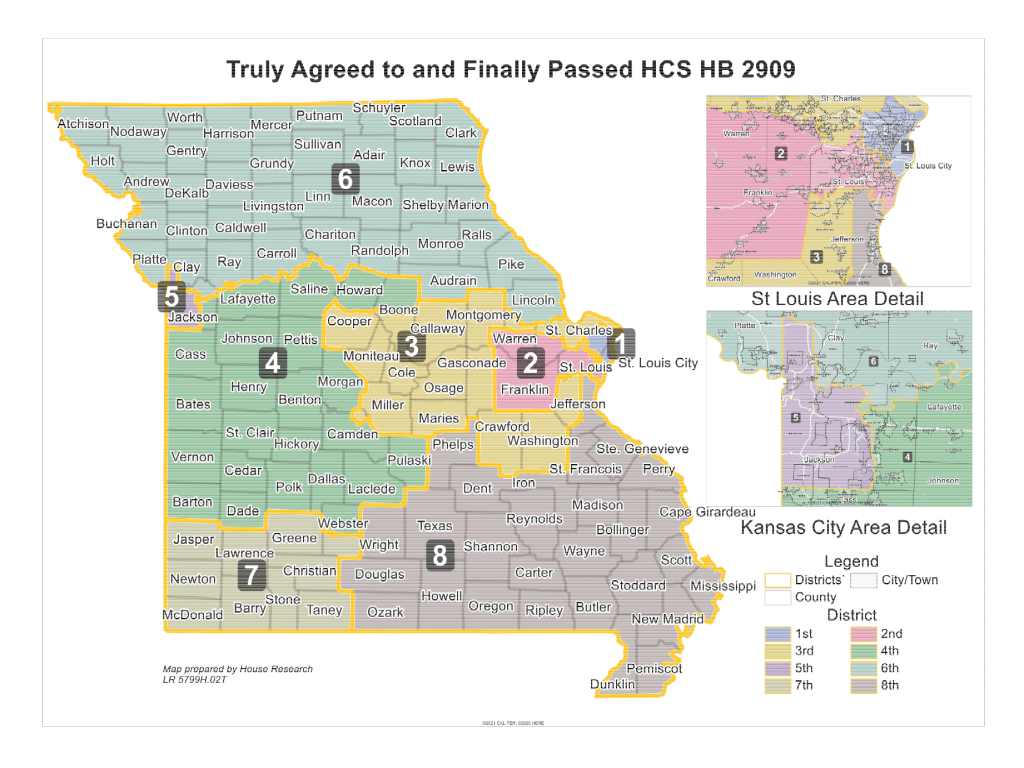

Gov. Mike Kehoe’s proposed congressional map

Raising awareness of the language in the state legislative redistricting section could ultimately backfire on proponents of the proposed map, Rostron said.

“The people who wrote the Missouri Constitution, when they wanted to say that the legislature has the authority to redistrict with some flexibility … they knew how to say that,” he said. “They specifically said it in that provision about state legislative districting. That strongly suggests that where they didn’t say it — about federal congressional districting — they didn’t mean it and they didn’t want it.”

A better argument, Rostron said, was one raised by Rep. Darin Chappell, a Rogersville Republican, during House floor debate: “Unconstitutional implies that the constitution has prohibited an act or concept.”

“The constitution being silent on a thing cannot make it unconstitutional. It can be extraconstitutional. But unconstitutional says that there is something in the constitution that says ‘thou shall not,’ and that is not the case here,” Chappell said.

Rostron said the use of the word “shall” in the constitution leaves some room for interpretation.

“You could make a pretty interesting argument that … they were saying it’s mandatory that you do this after the census (but) not foreclosing redistricting being done at other times,” he said.

He likened it to a parent telling their child that they can play videogames after they finish their homework and the child proceeding to play videogames first because “you didn’t say anything about whether I could play them before I do my homework.”

Courts have made decisions on similar questions about legal language, he said.

“In the U.S. Constitution, it says Congress has the power to declare war. It doesn’t then have an additional sentence that lists everyone else who can’t declare war. It doesn’t go on to say: ‘The president does not have the power to unilaterally declare war. The Supreme Court does not have the power to declare war,’” he said. “It assumes that, by saying Congress has the power to declare war, we are to understand that it alone has the power to declare war.”

“It’s not the same language — it’s not even the same constitutional document — but there is certainly a precedent for that kind of situation,” he said.

What happens if the new map goes to court?

Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, a Democrat who represents the Kansas City area in the U.S. House, has promised to go to court if the state legislature passes the proposed map, which would significantly change his district and put his reelection at greater risk.

Cleaver noted the proposed map would weaken the state’s largest city by splitting it among three districts. It also follows the city’s historic racial dividing line along Troost Avenue, pushing many of the city’s communities of color into a predominantly rural congressional district.

“Democrats have said we’re going to fight fire with fire and that’s exactly what’s going to happen,” Cleaver said during testimony Thursday at the Missouri Capitol. “But I want to warn all of us that if you fight fire with fire, long enough, all you are going to have left is ashes.”

The U.S. Supreme Court has previously heard challenges to state congressional districts. But it has decided that the U.S. Constitution doesn’t say enough about state redistricting to make the issue a federal one, leaving the matter to the states except in cases where federal statutes have been violated.

“Democrats have said we’re going to fight fire with fire and that’s exactly what’s going to happen. But I want to warn all of us that if you fight fire with fire, long enough, all you are going to have left is ashes.”

U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, Democrat from Kansas City

That means that if the map is challenged, it will go to the Missouri Supreme Court, which in 2012 heard a challenge to the state’s newly drawn 2010 map.

That challenge focused specifically on the compactness of the map, alleging that the state legislature had failed to meet the constitutional requirement that districts be “as compact as may be.”

In the constitution, compactness refers to counties having a somewhat regular shape, like “what the districts look like in Iowa, where they have nonpartisan redistricting and the whole state is basically just divided into rectangles,” Rostron said.

“It’s not like this Missouri map or other maps where they’re obviously not simple. We don’t even have a name for the shapes that they are,” he added.

However, the Missouri Supreme Court in the 2012 case decided that the districts, while not as compact as possible, were compact enough.

“They said ‘as compact as may be’ … is not just about geometry and having a square shape or a rectangular shape. You can take into account natural boundaries like rivers and try not to divide a city right in the middle,” Rostron said. “They found it means that the territory is somewhat closely united, not that it’s perfect in its physical shape.”

Both Deaton and Kehoe have praised the proposed map as being more compact than the current one. But Rep. Kathy Steinhoff, a Democrat from Columbia, said she didn’t believe it was much of an improvement.

Steinhoff said that after further research, she found that while several of the districts in the new map were more compact than they are under the current map, others were less compact, and two remained unchanged.

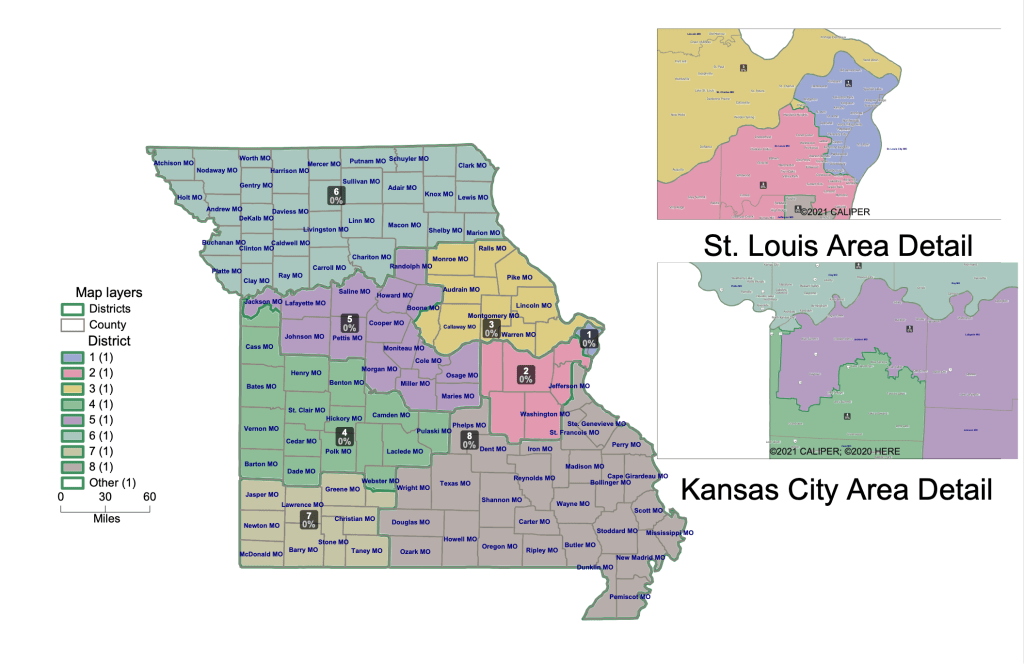

Missouri’s current congressional map

Under the proposed map, Jackson County voters would be pulled into districts stretching south to Springfield and east to Jefferson City.

In addition to being a constitutional requirement, compactness is a factor in the Princeton Gerrymandering Project’s scoring of states’ district maps. The study gave Missouri’s current map an “A” for its overall partisan fairness but a “C” for the geographic features, including compactness, of its congressional districts.

While the burden to prove unconstitutionality would lie with whoever challenges the map, the government’s ability to argue its case would also play a major role, Rostron said.

“You’re not going to fool a judge. … If you go in, as a lawyer, and you cite that provision — Article 3, Section 10 — and you say, ‘It says here that for public convenience, we can alter the districts,’ and that’s all you say, you’ve made a misleading argument. The other side is going to slam you for it, and the judge is not going to appreciate it,” he said.

But according to Rostron, a “more clever, sophisticated argument” is possible.

“You acknowledge that that provision isn’t directly relevant, but then you try to make a more nuanced argument about why, in fact, you think it does shed some light on the interpretation of another provision elsewhere in the constitution,” he said.

In other states, legal challenges to maps seen as politically gerrymandered have received mixed reactions from their respective high courts.

“Places like New York, Ohio, Alaska (and) Maryland have had some political gerrymandering (and) it has been struck down,” Rostron said. “But there are other places, like Kansas and North Carolina, where they have said that it’s not really the business of the courts to question this.”

But Rostron also acknowledged that Missouri’s general conservatism — reflected in its Supreme Court, where a majority of justices were appointed by Republican governors — is likely to play a role in any ultimate decision.

While the 2012 case could provide some precedent for justices to point to in a future decision, any challenges regarding the legality of midcycle redistricting would be unprecedented, raising questions about what the court might rule, Rostron said.

He said he could see the decision going either way.

“If you had to bet money on how it comes out, I think I would bet my money that they uphold the districting that was done,” he said. “But it’s not absolute. It wouldn’t shock me, on the other hand, if they were troubled by it and looked at the language of the Missouri Constitution and decided that this wasn’t either as compact as may be, or it just wasn’t permitted.”