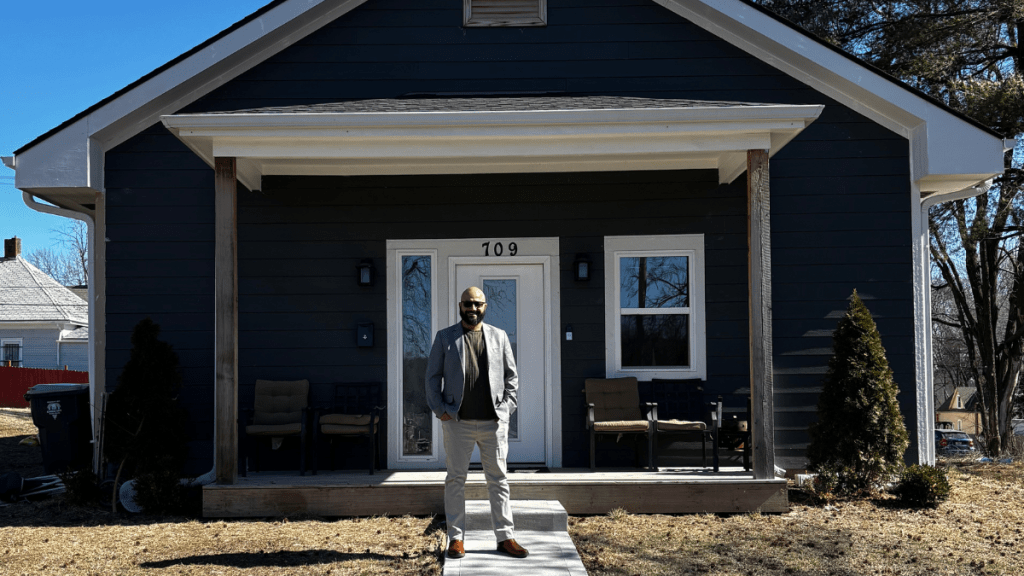

Reda Ibrahim has devoted his work to building affordable and sustainable housing in Kansas City. After immigrating from Egypt, he started RK Contractors LLC and co-founded the nonprofit Mercy in the City to do just that.

In 2024 new residents moved into a three-bedroom house he helped build in northeast Kansas City — one of the first new homes built in the Lykins neighborhood in decades. He didn’t just build it to be affordable. He wanted it to “pass every energy code in the country.”

He estimated that in a typical affordable home he works on in Kansas City, about 6% to 7% of the building cost goes directly to complying with the city’s energy codes. For the Lykins home it cost almost $20,000 to comply with city requirements.

Takeaways

- Kansas City Council voted 7-6 to roll back energy codes after single-family building permits fell.

- Single-family home permitting in Johnson County outpaced Kansas City by more than three to one in 2025

- The city simultaneously passed a second ordinance to study and likely adopt 2024 energy efficiency codes, meaning builders may have to adapt to new codes twice in the next year.

He built the home on property he owned for $285,000. He rents it out affordably and believes in building eco-friendly homes. But he’s conflicted over the added costs he sees as a contractor and his belief in building sustainable housing.

“I feel like I’m between two fires,” Ibrahim told The Beacon. “We can say ‘no codes’ so we can save money and build more. But the environment and the health of the houses would go down … I feel like we don’t have a middle ground here to stand on.”

Ibrahim’s predicament of balancing building costs against energy efficiency and environmental concern is at the heart of a debate that split the Kansas City Council this month.

In a 7-6 vote, the council passed an ordinance Feb. 5, rolling back portions of its energy code to loosen insulation requirements, relax energy performance targets and remove certain testing mandates for new residential construction. Mayor Quinton Lucas, who voted against the measure, allowed the ordinance to take effect without a veto.

Like cities across the country, Kansas City is grappling with an affordable housing shortage. Council supporters of the ordinance and trade groups that pushed for the change believe that loosening these restrictions will help spur new homebuilding with more flexible compliance metrics. But critics say the upfront building costs savings may not be passed on to homebuyers and ultimately will lead to higher utility bills for residents.

Billy Davies, senior field organizer for the Sierra Club Missouri chapter based in Kansas City, said that no developer has promised the rollback will actually reduce home prices.

“The question for all these codes is, ‘Who are we building for?’” Davies told The Beacon. “Is it really about maximizing the short-term profit of those making a development or is it about minimizing costs on customers?”

Kansas City tried to lead the region — alone

Kansas City adopted the 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) in 2023, which put the city at the front of the pack in the region for energy-efficient building standards.

The code required new homes to be sealed more tightly against air leaks, insulated more heavily, equipped with more efficient ventilation systems and subjected to additional inspections. For builders, it often meant upgrading from standard 2-by-4 framing studs to more expensive and wider 2-by-6 lumber to accommodate additional insulation.

Ibrahim’s project management partner Cesar Cea said that the average cost to comply with 2021 efficiency codes can run from $10,000 to $25,000 above standard builder grade depending on the compliance path taken.

The move led Kansas City to jump 10 spots in the national clean energy scorecard, rising to number 26 in the country, according to public testimony from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

The hope was that neighboring cities would follow Kansas City’s lead.

They did not.

Other municipalities like Overland Park, Olathe, Lee’s Summit, Blue Springs and Independence all kept their less restrictive energy codes. What was supposed to be a regional shift became a competitive disadvantage, according to backers of the loosening of the energy code. A builder could simply opt to build outside of city limits with fewer restrictions, and many did just that.

The stricter code took effect in the fall of 2023. For more than three months afterward, the city did not issue any new single-family building permits under the new rules. Before adopting the codes, Kansas City averaged 66 such permits a month in the four prior years, according to local builder Brian Tebbenkamp in testimony to Congress.

During the Kansas City Council’s recent debate, Councilman Crispin Rea laid out the trend. Kansas City had a rush of applications ahead of the new codes in 2023, then saw a nearly 50% decline in 2024, and recovered only slightly in 2025.

The comparison to the rest of the metro area was even more striking.

According to data from the Home Builders Association of Greater Kansas City, in 2025 Johnson County — with a population of 620,000 — issued 1,851 residential building permits for single-family homes. Kansas City, Missouri, with roughly 500,000 people, issued 499 such permits over the same period. Lee’s Summit and Blue Springs combined for just 51 fewer single-family residential permits than Kansas City despite having one-third the combined population.

Energy codes are only a piece of the puzzle

The permitting numbers are real. But suburban cities tend to have more undeveloped land and room for large subdivisions than most of Kansas City.

A litany of factors such as tariffs, inflation and higher interest rates have also put a squeeze on homebuilding in recent years. And many close to the issue locally say that the biggest barrier to building in Kansas City wasn’t the energy codes, but the city’s sluggish permitting process.

Gabe Perez, president of the Unified Contractors of Kansas City, attended early stakeholder meetings on the energy code debate. He said the energy standards had some effect on the slowed pace of building in the city but said that’s not the whole story.

“The real issue is, and has been, even before adoption (of the 2021 IECC energy code), is the permitting process and functions over at the planning and development department,” Perez told The Beacon. “That’s what I’ve been hearing for years.”

Ibrahim agreed. He listed four barriers to building affordable housing in Kansas City: bureaucracy, energy codes, access to capital and workforce readiness.

“Frankly, affordability is a challenge because labor and material costs are so high and wages have stayed low,” Cea said. “What it costs to build things is just so skewed right now that even if we didn’t have these energy codes, even if the city was more efficient, it doesn’t close that gap, still.”

Ibrahim said Kansas City’s planning process takes anywhere from six to eight weeks to approve plans. He said in other neighboring cities that process can take only a week or two.

Even those who cautioned against blaming the energy code alone acknowledged the permit data was hard to dismiss, and that the code did incur costs to builders.

The current energy code, Ibrahim estimated, tacked on costs for insulation materials, thicker lumber for walls, time spent managing additional inspections and the specialized labor needed to meet standards. All those costs add up.

Resident costs

The housing cost equation has two sides: the builder’s cost and the resident’s occupancy costs.

Energy auditor Sharla Riead argued against the rollback in a Kansas City Star editorial, writing that utility bills are the second-biggest household expense and that homes aren’t affordable if heating and cooling bills are too high.

According to federal data cited by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, homes built to the stricter 2021 standard would save households $1,200 a year on utility bills compared to homes built under the outdated 2009 code.

The group also cited 2019 American Housing Survey data that found the median low-income homeowner in Kansas City spent more than 8% of their income on energy for their home when the national average is 3%. They said that rolling back codes would mean perpetuating a cycle of financial strain “that forces families to make impossible choices between basic necessities.”

Beth Pauley, a former member of Kansas City’s Climate Protection Steering Committee, submitted two rounds of public testimony, one against loosening energy codes and another urging Lucas to veto the ordinance.

“In this economy, policies that lower utility costs are a no-brainer,” Pauley wrote.

Davies of the Sierra Club said that this local ordinance comes as federal and state governments are scaling back climate protections. He said loosening of restrictions is a cost borne by the residents of Kansas City.

“These actions serve to put more short-term profit into the hands of well-off companies while passing the costs onto people —– through higher energy bills, exacerbated health expenses and worsening air quality,” Davies said.

Jeremy Nelson with the Kansas City Chapter of the American Institute of Architects testified that the city should skip the rollback and move straight to adopting the newer 2024 energy code since it has modifications for upfront affordability and gives builders more options to hit energy efficiency scores. But he acknowledged that local amendments could be made to the 2024 code if evidence-based compromises are needed.

‘Let builders build’

The rollback of energy codes comes after a sustained lobbying effort by the local Home Builders Association.

The HBA has been a consistent foe of the more restrictive energy code. The cause was taken up by two council members, Nathan Willett and Wes Rogers, who represent Kansas City’s Northland, which has more undeveloped land compared to the rest of the city. The two sponsored the ordinance that was ultimately passed to roll back energy codes.

The ordinance came after a December resolution sponsored by Willett, Lucas and Rea directed City Manager Mario Vasquez to develop recommendations to align the energy codes with surrounding municipalities in 45 days. During that time the HBA launched a “Let Builders Build” website and pressure campaign.

Will Ruder, executive vice president of the local HBA, said in an emailed statement to The Beacon that the original code adoption without any local amendments caused permitting activity to decrease 54% while 78% of builder companies halted operations in the city. Meanwhile, he said, permitting in the rest of the metro area increased 14%.

“The Kansas City Council’s recent approval of amendments to the city’s energy code will hopefully help to increase residential construction in the near term,” Ruder said. “Frankly, I was disappointed but not surprised by the level of vitriol and outrage publicly expressed toward the supporters of the ordinance and the mayor considering the modesty of the amendments to the energy code themselves.”

A divided council

Councilwoman Andrea Bough, who had championed the 2021 IECC code adoption before it was enacted a few years ago, said the council was short-circuiting a process it had already put in motion.

She co-sponsored an ordinance that passed unanimously to examine the 2024 IECC codes — a newer edition that is somewhat less rigid than the 2021 version — and funded community engagement efforts to align the city with neighboring municipalities. That process is expected to take six months to a year.

“Wouldn’t changes now and changes in six months, arguably … add confusion and cost to the process?” Bough said. “I don’t see any reason for us to make this change and then come back in six to nine months and make a different change.”

Councilman Johnathan Duncan also opposed the rollback, arguing that surrounding cities were beginning to move toward the 2024 energy code. He said he and Councilman Eric Bunch spoke with members of the Overland Park City Council and that Johnson County as a whole appeared to be moving toward adopting the 2024 codes.

“We are a leader in this region. We set a tone,” Duncan said. “People are going to build where it is easiest, but it doesn’t make it the right thing to do.”

Bunch took aim at what he called the “red herring” of state preemption — the argument that the city should act now because the Missouri General Assembly might strip local governments of the power to set their own energy codes.

Rea, who ultimately voted for the rollback, was the most candid about the tension between housing and environmental concerns. He framed the choice against the city’s own climate action plan, which he said allocates roughly 2% of its carbon reduction targets to residential building codes.

“The question for myself is, ‘Is that 2% worth a housing crisis or exacerbating a housing crisis?’” Rea said.

When fielding questions from Bough, Willett said that he’d like to see more housing in the city.

“I don’t think that you understand the challenges that constituents are having up in the Northland in trying to do single-family homes,” Willett said. “It’s not affecting the people who are building those $1 million-plus homes in the Shoal Creek area. … What we’re doing is we’re losing a lot of starter homes coming into our city.”

Councilman Kevin O’Neill said Bough had a very thorough process and did everything right when implementing the 2021 code. But he still wanted to move forward with loosening the energy code.

“I think we’ve had four or five years to see the impact of it, and that’s the only reason I am strongly in favor of going forward with this,” O’Neill said. “Because I think we’ve seen the (loss of) a lot of the builders to other municipalities.”

Councilwoman Melissa Patterson Hazley says she’ll believe in regional cooperation when she sees it.

“We’re in a competition to remain the best city in the region, and we are, but we are dealing with partners that want our stuff,” Patterson Hazley said. “We’re getting played. We’re getting duped.”

The fight ahead

The same day the council passed the rollback it also passed an ordinance to examine the 2024 code, engage in a formal public stakeholder process and have the city manager return with recommendations.

The 2024 code, shaped in part with input from the National Association of Home Builders, is broadly seen as stronger than what Kansas City adopted under its latest amendments, but more flexible than the unamended 2021 version.

As noted from several throughout the process, many in the region are expected to adopt the 2024 energy codes.

Davies said the city must use the coming process to “correct course” and adopt a code that is “good for residents, not just one that maximizes short-term profit for industry at all costs.”

Ruder with the builders said he applauds the city for taking steps to align energy codes that “better fit the region.”

“We look forward to working with the city to receive guidance on implementation in the coming days,” Ruder said. “And stand ready to participate and engage in the upcoming code review, amendment, and building and energy code recommendation processes.”

Ibrahim, who recently signed a contract to build two more affordable houses in Kansas City, hopes that every city in the area can get on the same page.

“This would be brilliant, the smartest decision they could ever make,” Ibrahim said. “If you can make my life simple, I would be happy.”