Health care costs are rising in Missouri and Kansas, especially for workers who get coverage through their employers.

In both states, families who get their health care through work are paying nearly 10% of their annual income toward health insurance premiums and deductibles, a new report from the Commonwealth Fund found.

In Missouri, the cost of premiums and deductibles combined ate up 9.6% of a family’s household income when they were enrolled in health insurance through their employer in 2024. In Kansas, 9.9% of household income went toward premiums and deductible costs, the report found.

“What does affordable mean?” said Timothy McBride, a professor and health economist at Washington University in St. Louis. “We don’t have a real clear answer for that, but 10% (of household income) gets kicked around a lot.”

“It’s pretty mind-boggling when health care costs are hitting it across most of the country,” McBride said.

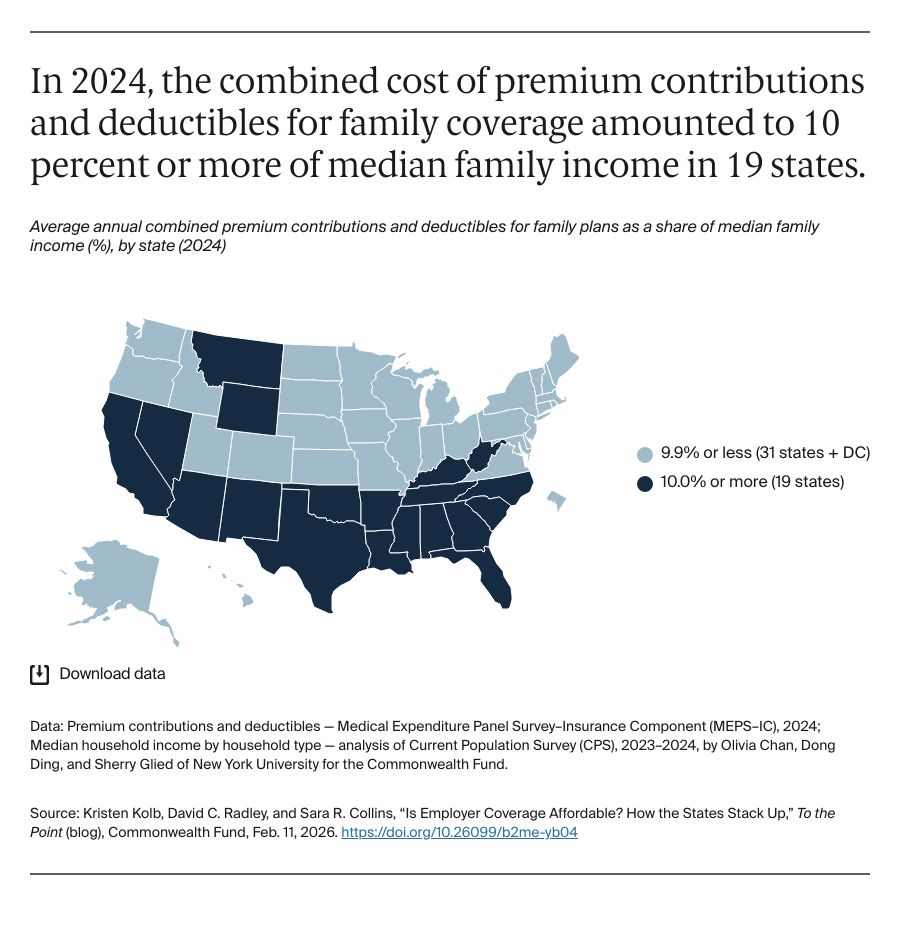

In 19 states, families were paying 10% or more of median household income toward those health care costs throughout 2024.

For individuals enrolled in health care through their employers, 26 states, including Kansas and Missouri, saw employees paying 5% or more of their annual income toward out-of-pocket health care costs.

In Missouri, deductibles for single coverage were 5.4% of the median household income, while in Kansas, deductibles were 5.5%.

“If you’re spending 5% of your annual household income on your health insurance deductible, I could see the argument being made that you’re underinsured,” said Linda Sheppard, a senior analyst and strategy team leader at the Kansas Health Institute. “Because that is just a huge financial burden.”

“If your annual plan, and your deductible, is high enough that it’s taking out that much of a chunk of your household income every year, you run the risk of people … not going to get that service or that care, because I know I’m going to end up having to pay that bill,” Sheppard said.

How do Missouri and Kansas stack up on health insurance affordability?

Even in Missouri and Kansas, where premiums aren’t as high as in other states, residents are sitting right at the threshold of affordability.

Overall, the states are following the trend of increasingly expensive health care across the country, said Kristen Kolb, a research associate at the Commonwealth Fund. And that’s before factoring in the cost employers are paying for that care.

“That’s only a fraction of what the total cost for this coverage is,” Kolb said.

In 2024, health care spending in the U.S. reached $5.3 trillion and increased 7.2% from 2023. That was following a previous increase of 7.4% from 2022 to 2023. Health care spending during those years outpaced overall economic growth — making up 18% of the share of economic activity in 2024.

That comes after a handful of slow years of spending on health care following the COVID pandemic.

“When health care costs are going up that high, you’re going to see it reflected in premiums,” McBride said.

A higher share of patients with chronic disease, increased pharmaceutical spending and a lack of competition throughout the market are major factors driving costs higher.

“Health care marketplaces and insurers that have less competition tend to have higher costs and premium growth,” McBride said. “If you have dominant health systems that can charge prices without getting a lot of pushback, that’s not generally that good.”

For the most part, insurers can pass along those rising costs to consumers. In this case, employers are feeling the pinch from all sides as health care costs and spending continue to rise.

For larger employers, it’s generally easier to try and keep employees from paying those higher costs. Still, as health care costs outpace wage growth, the costs will ultimately get passed along again from employers to employees.

“These costs continue to rise for employees because companies are just trying to share more of their costs,” Sheppard said. “There aren’t really a whole lot of other options. If you’re the employer, you raise what your employees are paying, and you try to reduce the richness of your benefits or your plan.”

“You’re going to see that number continue to edge up of what individuals and families are having to pay out of pocket for their health care,” Sheppard said. “I don’t see that as changing, because the cost of care continues to rise over time.”