The images have become ubiquitous in the Trump administration’s campaign for mass deportations of immigrants.

Masked agents, swathed in tactical gear and carrying semiautomatic firearms, menace protesters with chemical sprays and smash car windows while dragging immigrants from their vehicles.

Takeaways

- Some legal experts believe prohibiting federal law enforcement from masking their identities is not settled law, despite the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

- Law enforcement is seeking to strike a balance between a tradition of requiring police to wear badges and nameplates and modern realities like COVID and doxing.

- Social scientists have spent decades studying how masking or shielding the identity of soldiers, police and others has links to aggressive behavior.

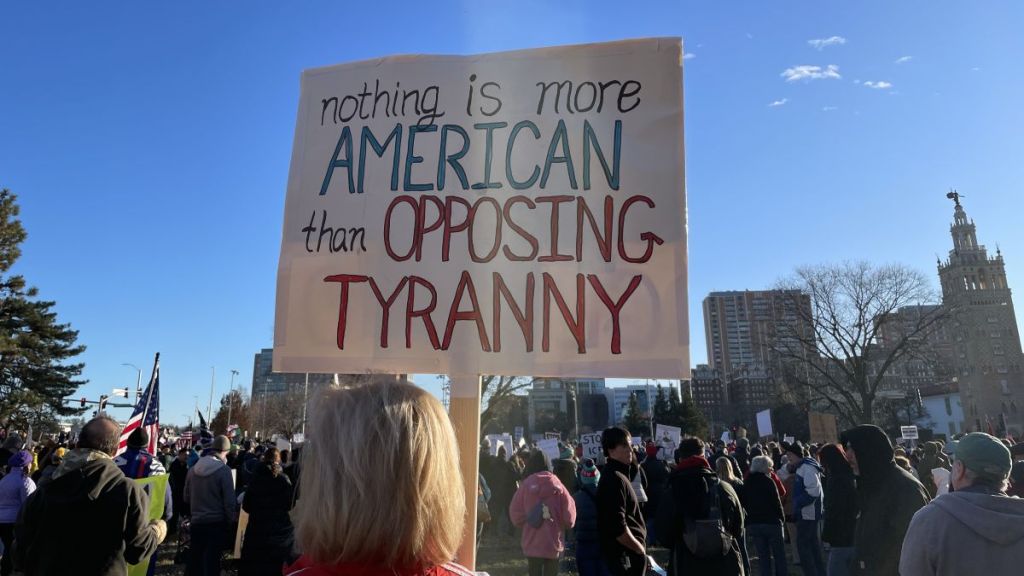

Critics label the aggressive actions by unidentifiable agents as a calculated effort by the Department of Homeland Security to send a paramilitary force into select American cities.

But the cheapest and most basic part of federal agents’ gear — face coverings of knit and cloth masks — is the focus of legislation at the federal level, in statehouses and smaller municipalities across the nation, including in Jackson County.

“We’re going to have to deal with the issue before the issue deals with us,” said Jackson County Legislature Chair Manny Abarca IV.

Abarca introduced a proposal requiring law enforcement to keep their faces and badges visible and is backing an amendment narrowing the focus to federal agents conducting immigration enforcement within the county.

County legislators are scheduled to hear public comments at 3 p.m. on Feb. 9.

The Jackson County ordinance mirrors efforts nationally, carving out exceptions for SWAT and other specialty teams, undercover work and the use of helmets with shields for officer safety. Those efforts have gained momentum since the recent shooting deaths of Alex Pretti and Renee Macklin Good during an ongoing immigration enforcement crackdown in Minneapolis.

Supporters believe mask bans will help deescalate tensions between the community and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement by ensuring that immigration agents are identifiable and accountable.

Decades of social science research supports the contention that masking a person can facilitate aggressive behavior. Outcomes have been studied with children, in law enforcement, in the military and in conflicts around the world.

Homeland Security is pushing back against local and state bans.

Primarily, the government cites the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, which guards against state laws that conflict with federal.

Legal experts disagree on the legality of banning mask-wearing by law enforcement.

They are split on whether the Supremacy Clause is a full shield for an immigration agent’s use of masks while detaining immigrants.

In Jackson County, legal counsel is continuing to study the issue, acknowledging that this is a new type of law.

National policing agencies are also weighing in, at times moderating prior messaging. They seek to strike a balance between maintaining public trust by having officers identifiable and supporting officer safety in an era of doxing.

Municipal police have long worked to differentiate themselves from federal immigration agents. They emphasize that members of immigrant communities can be perpetrators of crime, witnesses or victims. Maintaining trust and relationships is imperative.

Police departments have a tradition of requiring identifiable uniforms, badges and having the officer’s name prominently displayed.

Jackson County Sheriff Darryl Forté believes the proposed ordinance is unenforceable.

Forté is concerned about scenarios where his deputies would be required to issue citations to federal agents. He doesn’t want deputies accused of interfering with federal investigations, noting “it could create a situation where both deputies and federal agents attempt to detain one another, leading to a dangerous confrontation.”

The International Association of Chiefs of Police recently issued a statement underscoring that immigration enforcement is a federal responsibility.

The organization cautioned officers during COVID to be aware of the impact of masks, noting that facial coverings, even surgical ones for health reasons, can be intimidating and diminish transparency to the public.

The organization hasn’t backed off from that stance.

“The use of face coverings and the absence of visible identification during enforcement operations can create confusion, fear and mistrust among community members and responding agencies, potentially increasing operational risks and eroding public confidence,” a recent statement read.

But the association is also addressing doxing fears and suggests substituting officer names in some cases for alphanumeric codes or badge numbers.

In late January, the association asked the White House to convene national, state and local policing representatives for policy discussions to find “a constructive path forward.”

Democrats, in recent budget talks, demanded that immigration agents stop masking in exchange for votes to end a partial federal government shutdown.

U.S. Sen. Eric Schmitt of Missouri quickly replied to the demand in a video posted on social media.

“There is no way in hell we’re going to let Democrats kneecap law enforcement and stop deportations in exchange for funding DHS,” Schmitt said.

Public trust balanced against threat of doxing

In Washington state, proposed legislation to ban law enforcement’s use of masks has passed out of the Senate. Washington is among at least six states that have or are considering banning masks for law enforcement, including Massachusetts, New York, Illinois, Tennessee and Michigan. A mask ban is included in a Democrat-backed measure in the Republican-controlled Kansas House.

California was the first state to pass a law in 2025. The No Secret Police Act bans the use of face masks by law enforcement in California. Exceptions include health considerations, such as a face covering to protect officers against fumes or dangerous chemicals.

The California measure was quickly challenged in November 2025 with a lawsuit by the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Justice.

The federal government said the California law is unconstitutional, anti-cop and a danger to law enforcement.

DHS stresses that agents clearly identify themselves as police, usually by their vests, which are marked “ICE/ERO” or “Homeland Security.”

“The sanctuary politicians of California want to make it easier for violent political extremists to target our brave men and women of federal law enforcement for enforcing immigration laws and keeping the American people safe,” DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said in a statement.

“This demonization is going to get somebody killed.”

Threats to public officials, both elected and law enforcement, were underscored with two indictments returned by a federal grand jury in late January.

A 23-year-old Wichita man was accused of posting a video on social media threatening to assault and murder federal ICE agents working in Wichita.

In a separate case, the same grand jury also returned an indictment for a 60-year-old Wichita man who is accused of stating his intention to murder U.S. Rep. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota.

Omar, a vocal opponent of President Donald Trump, was rushed and sprayed with a liquid by a man during a town hall on Jan. 27.

Her attacker was tackled, taken into custody and has since been charged in the incident. Omar was unharmed.

U.S. Attorney Ryan A. Kriegshauser issued a statement along with the two Kansas indictments, underscoring an intolerance to political violence, no matter the target.

“In a democracy, we settle our differences at the ballot box after robust public debate,” Kriegshauser said. “For our system of government to work, it’s vital that certain lines are not crossed when it comes to self-expression. Threats of political violence destabilize the very core of our system of governance.”

Gaiters, balaclavas and gas masks

Gaiters, simple tubular pieces of cloth that cover the neck and face, can be purchased in packs of two for less than $10.

Balaclavas, which also cover the head, are similarly affordable.

Both garments are commonly used to protect hunters and others from cold and sun. But they have been adopted by federal agents detaining immigrants for deportation.

Gas masks are often worn also, further obscuring the agents’ faces.

Supporters see the bans on such apparel as a method to help deescalate tensions, forcing the agents to be identifiable and accountable for actions like shoving people or spraying them with chemical irritants.

Research supports that contention.

Anonymity, a reprieve from being held accountable for individual actions, has long been studied.

The process that researchers study is deindividualization. They attempt to measure how shielding identity can make people less self-conscious and more vulnerable to groupthink and has an impact on the ego.

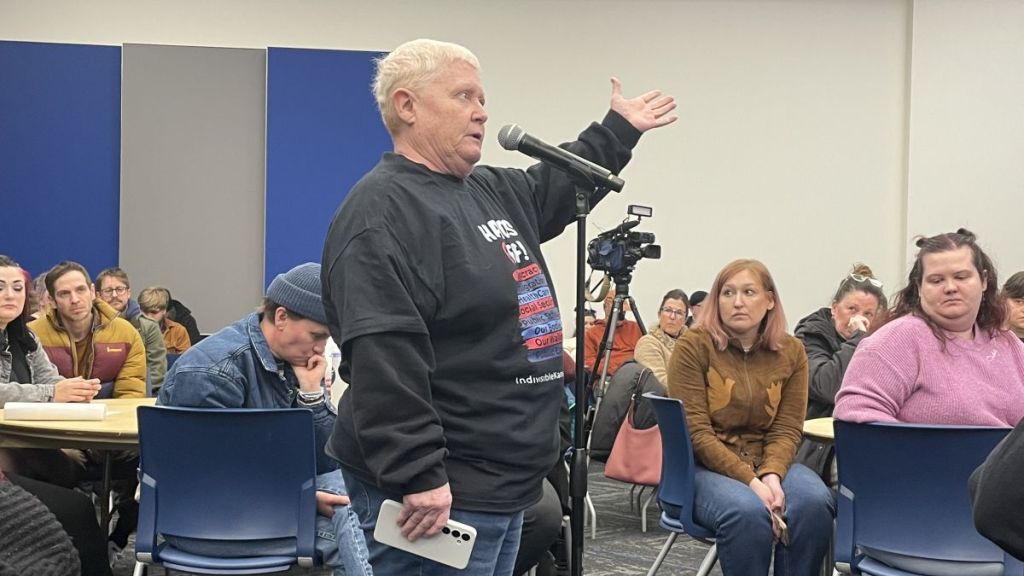

The research looks at what types of things can change a person’s psychological state so that they are more likely to inflict harm on other people, said Lauren Yan, a Kansas City resident.

Yan was among more than 150 people who testified at a recent town hall on Jackson County’s proposed ordinance.

Yan’s own research on migration has taken her around the world. Her dissertation focused on Syrian refugees living in Jordan.

“Anthropologists have looked at this across cultures comparing war practices,” Yan said. “The groups that changed their appearance before battle, either using paint or masks or something similar, tended to inflict higher aggression in many ways.”

A Harvard study, “Investigation Into Deindividuation Using a Cross-Cultural Survey Technique,” found that self-control can be lost with “a feeling of anonymity and a consequent lack of concern over social evaluation which allows the individual to act aggressively.”

Other studies have focused on specific conflicts, like Ireland.

And some were completed in lab conditions. Researchers measured actions when people wore lab coats with hoods to conceal their faces and were asked to administer electric shocks to other people. The victims were portrayed as nice or obnoxious.

The hooded participants were much more likely to administer the shocks than people whose identities were not hidden.

Pondering the Supremacy Clause

Even supporters of the Jackson County proposal question whether the county’s efforts will result in a failed, and expensive, legal challenge.

The point was made repeatedly at the recent town hall.

The Supremacy Clause instructs that federal law takes precedence over conflicting state laws.

The State Democracy Research Initiative at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has been studying the issue.

In January, it updated a deep legal analysis first issued in October 2025, reflecting new ordinances being proposed to counter ICE.

“Because the legal doctrine is murky, it is difficult to predict how legal challenges to mask bans might play out,” according to the paper, “Can States Prohibit Federal Law Enforcement From Masking on the Job?”

The Supremacy Clause says states can’t interfere with or control the operations of the federal government, an obvious hurdle for any ban.

The paper doesn’t downplay the challenges of the Supremacy Clause.

But the research also points out that states — or in this case a county — have their own constitutionally grounded powers and interests, including interests in safeguarding the well-being of their residents and preventing federal overreach.

The courts will likely weigh whether masking is necessary for federal agents to do their work, and whether a ban would equate to a state trying to regulate the federal function of immigration enforcement.

The paper also cites Erwin Chemerinsky, a constitutional scholar and dean of University of California Berkeley School of Law. Chemerinsky has written opinion articles assessing the constitutionality of the California law that is now before a court.

In addition to deep legal analysis, he also points to how ICE agents have operated under previous administrations.

“ICE agents have never before worn masks when apprehending people, and that never has posed a problem,” Chemerinsky wrote.

The public can express their views on the proposed mask ordinance at a public hearing at 3 p.m. on Feb. 9 at the Eastern Jackson County Courthouse in Independence. The hearing will also take public testimony on a proposal to place a moratorium on any approvals for non-municipal or county detention centers through 2031. That effort is targeted at a south Kansas City warehouse that is being sold to the federal government for use as a detention center for up to 7,500 immigrants.