Monica Curls still remembers being about 10 years old waiting around after Chiefs home games to get autographs from players on the team.

Takeaways

- The Kansas Department of Commerce estimated more than 2 million people would go to the stadium district without tickets to a game. Economists doubt that.

- Kansas said the stadium will bring $4.4 billion in economic impact from construction alone. That’ll create 20,000 construction jobs and nearly 4,000 permanent jobs, the state says.

- The Beacon tried to speak with the group that calculated the economic impact report the state used. The company never responded to requests for comment.

“I had something signed by Deron Cherry, and I had something signed by Steve DeBerg,” said Curls, a member of the Kansas City Public Schools board. “These were, like, 1980s people — ‘80s and ‘90s.”

Curls said her family has had season tickets since 2007. They also had season tickets in the 1970s when the Chiefs first moved into the Arrowhead Stadium, but those seats weren’t as good so the family got rid of their season tickets. They kept showing up for games, though.

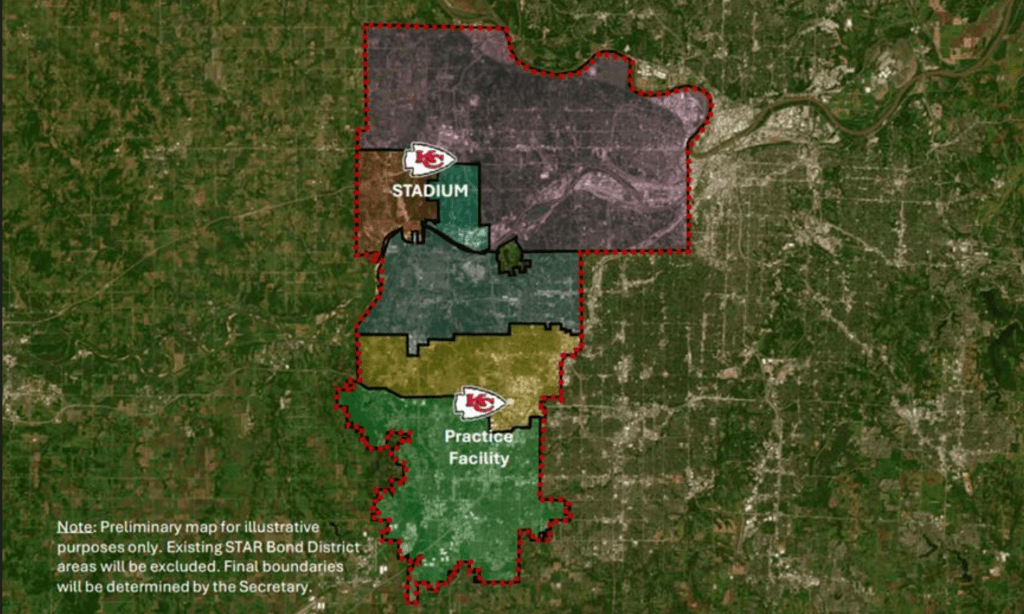

The Chiefs have announced plans to leave Missouri after getting more than $2 billion in incentives from Kansas. The team is expected to build a stadium in Wyandotte County and a mixed-used development in Olathe with a practice facility and team headquarters.

Kansas has offered to finance 60% of the multi-billion dollar project, or $1.8 billion in bonds for the stadium and another $1 billion in bonds for other projects.

One economist says this is the largest public subsidy of a professional sports stadium in American history. And Kansas did this to entice fans like Curls, and all the generations of her family, to spend their money in Kansas instead of Missouri.

The Kansas Department of Commerce estimates the team will bring in $4.4 billion in economic development during construction and another $1 billion every year the stadium is in Kansas.

Economists have long been skeptical about spending tax dollars to lure sports teams. They consistently warn that professional sports don’t bring in as much money as advocates claim.

Now that the deal is done, The Beacon asked the state for every economic impact report, study or piece of data they used to calculate the team’s benefit to Kansas.

The Beacon then showed that data to four economists, including one who said the state’s calculations were “incredibly optimistic, to be polite.”

“I laughed for quite a while after I saw (their math),” said J.C. Bradbury, a professor of economics at Kennesaw State University.

“It’s just insane,” said Dennis Coates, a professor of economics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “I don’t know how to put it any other way. The numbers are just not credible.”

Bringing people to Kansas

Kansas used its Sales Tax and Revenue Bonds program to entice the Chiefs. That program uses future sales taxes extracted from a STAR bonds district to pay off debt.

Supporters have argued that unless someone went to a Chiefs game, their tax dollars wouldn’t pay for the stadium. They also said that building the stadium would bring in enough people that it will pay for itself.

“It’s a great day to be a Kansas taxpayer because we pulled . . . all of this off without raising taxes on Kansas taxpayers, without using any base revenues from the State General Fund, and without pleading the full faith and credit of our state to the bonds,” said Korb Maxwell, an attorney for the Chiefs, in testimony before Kansas lawmakers on Wednesday. Maxwell called Kansas’ STAR bonds “tried, true and tested.”

Bradbury disagrees.

Kennesaw State University is in Cobb County, Georgia, which has Truist Park, home of the Atlanta Braves. Cobb County paid up to $300 million in the early 2010s to relocate the Braves from Fulton County to Cobb County, hoping for similar economic returns as Kansas is now.

Bradbury studied the move and said the county only got an extra $3 million in tax revenue from the stadium. That’s for a team that plays 81 games a year and has annual attendance numbers four times higher than the Chiefs.

“There’s no such thing as a free stadium,” Bradbury said. “You can’t just spend $1.8 billion of taxpayer money for free. You can’t pull that money out of thin air. It’s going to have to come from somewhere.”

The concerns of Bradbury, and other economists, fit in a couple of categories. They don’t think professional sports create enough new economic activity to pay off massive debt. But they are also critical of Kansas’ data that they say inflates the number of visitors the stadium will get.

Kansas officials estimate 3.7 million people would visit the stadium, headquarters and practice facility each year. By way of comparison, the Wichita River District drew nearly 3 million visitors in both 2018 and 2019. The Wichita project is currently paying back a $55.3 million bond and wouldn’t be able to pay off billions in debt.

Of the 3.7 million people expected to visit the Chiefs’ projects, 532,000 would visit for non-team related activities such as concerts, corporate events and other sports, the state said.

That suggests almost 3.2 million people would go to the stadium projects for Chiefs games. The Chiefs can host, at most, 15 home games in a season. That would include two preseason games, nine regular season home games, three playoff games and the Super Bowl — which doesn’t happen every year.

That means the state estimated at least 215,000 fans will show up each game, whether they had a ticket to watch the game or were at a nearby establishment. Economists say those numbers are ludicrous for a 65,000-seat stadium.

Curls, from Missouri, said Arrowhead Stadium is currently less than a 10-minute drive without traffic. On game days she can leave her house and get into the stadium in about 30 minutes. She is keeping her season tickets for now, but she is worried the prices will go up when the Chiefs move to a new stadium in Kansas.

If the team does build a 65,000-seat stadium, that is about 10,000 fewer seats than Arrowhead Stadium has now. She said that will jack up ticket prices, and there could be extra fees added on to buy season tickets. Curls is worried she’ll be priced out of season tickets.

Curls said she will try out the stadium district in Kansas, but probably not that often.

“That’s (15) potential additional days (in Kansas) out of 365,” Curls said, “And yeah, there’s some tax dollars associated with that. I don’t know if it’s going to be worth everything that they’re throwing at them.”

Spending money in Kansas

For Kansas, the math was simple. All of the game-day spending is happening in Missouri, and now that’s come across the border, said Robert North, chief counsel for the Kansas Department of Commerce.

“That’s all new spend to Kansas,” he said.

Game-day spending estimates vary depending on who is doing the math.

NJ.bet estimated the cost of going to a game at every stadium in the league. For Arrowhead, it estimated a fan who pays for parking, a hotdog, a beer and a ticket spends $184.55. That could mean $12 million in game-day spending every Chiefs game — and that isn’t counting merchandise or fans who buy more than two concession items.

The Action Network estimated that a family of four spends $1,690 for every game attended.

Sports marketing company Sports Value estimated the NFL’s 32 teams generate a combined $4.2 billion in game-day revenue. That’s the second highest game-day earnings behind Major League Baseball.

The Department of Commerce estimates tailgaters who don’t have tickets to the game will spend a projected $46.7 million each year. Day-trippers will spend $90 at the game while overnight travelers will drop between $222 and $376 during their stay.

Rob Guy lives in Prairie Village, Kansas, and goes to a Chiefs game about once a year. He watches most games at home with friends and family.

Guy wants to check out the new stadium district. He watched the Chiefs play in Arizona, and he liked the pregame options in Glendale. Whether going in person, staying home, Kansas or Missouri — Guy is watching Chiefs games.

Economists say this is one reason stadiums don’t create much economic development. One week Guy might be paying for parking and hotdogs at the new stadium. But the next week, he’s back at home buying things from the local grocery store in preparation for the game. People are spending money with or without the stadium.

Guy, also a KC Current fan, said he has driven up to the riverfront development by the soccer team’s stadium because of some of the options there.

He said he wants to see unique local restaurants near a Kansas-based Chiefs stadium. Guy said he has chain restaurants near him already, and he isn’t heading up to the next county over to get the same options. But it was unique options that brought him out near the Current district without a game happening.

“It’s like shipping containers, and they have a cocktail bar called Moonstone,” Guy said. “But that’s an example of somebody local that’s doing a bar concept. That’s not like a Buffalo Wild Wings.”

Making Kansas a tourist destination

There are Chiefs season ticket holders from 10 different states, according to state data provided to The Beacon. Football stadiums will bring in people from outside the Kansas City area, said North, with the Department of Commerce.

Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly has said when touting the Chiefs move that Kansas is “not a flyover state, we are a touchdown state.”

The Department of Commerce estimated 28.3% of people who visit the stadium will come from out of state and 32% will come from 100 miles away.

Daniel Kuester, an economics professor at Kansas State University, could be one of those 32% of people who travel 100 miles.

It isn’t clear where exactly the stadium will be in Wyandotte County. But Manhattan and Emporia are about 100 miles away from the area. That’s only an hour and a half drive. Wichita is two and a half hours away.

Kuester said if he was going to a game, he’d buy all his tailgating supplies at the grocery store in his hometown. Then he’d head over to the stadium. The same goes for someone living in Missouri who fills up the car before making the drive to the stadium.

“You’re also assuming that everybody that comes to a Chiefs game is going to spend all this money in the vicinity of the stadium,” Kuester said.

Kuester noted that some football tourists may land at Kansas City International Airport and rent a car in Missouri. Out-of-state tourists could get a hotel in Missouri and spend dollars there.

New jobs

The Chiefs have a 30-year lease on the stadium. If state estimates are correct, the lion’s share of economic development will be from regular season activity. But the state does expect $4.4 billion in economic impact from construction alone.

North said it will create 20,000 short-term construction jobs, and those workers will be driving to Kansas every day passing restaurants, gas stations and convenience stores. That doesn’t even count all the work companies will get.

“It’s construction labor and that activity is taking place in Kansas,” he said, “100% of that activity is going to take place in Kansas.”

Then come full-time employees who work at the stadium and for the team. The economic impact report said the stadium projects will support 3,990 jobs in Johnson and Wyandotte counties. Kansas expects to collect $61.8 million in annual income tax, the state said.

Roger Noll, a professor of economics at Stanford University, said the 20,000 construction jobs figure is about right. But those aren’t all necessarily a net increase in jobs in Kansas.

Economists argue those people would be working anyway. They would simply be building a stadium instead of other projects. And there was going to be stadium construction anyway, because the Chiefs wanted to build a new stadium or renovate Arrowhead if the team stayed in Missouri.

The Chiefs didn’t move that far away, so it really won’t create many Kansas-based long-term jobs with the team because everyone who already works at the stadium will keep their jobs, he said.

And the long-term jobs aren’t great, Noll said. Sports teams hire only a few thousand people. And the game-day staff, like ushers and hotdog vendors, only work a few hours a day about a dozen times a year.

Bradbury, with Kennesaw State University, expects this deal will hurt Kansas taxpayers in the long run. He was skeptical of any incentive package to lure a team before it was approved. Now that it has been approved and he’s seen the state’s projections, he remains pessimistic.

“It’s like asking me if two plus two equals ice cream,” he said. “These are nonsense numbers. It’s just made up.”

The Beacon contacted the firm that calculated economic development data on the stadium, but they didn’t reply to requests for comment.

“When you ask me to evaluate the number,” Bradbury said, “my response is sort of this isn’t the way we would look at this to begin with.”