Aug. 29, 2025, update: Just after 4 p.m. on Aug. 29, Gov. Mike Kehoe announced he was calling state lawmakers back to Jefferson City on Wednesday, Sept. 3, for a special session focused on congressional redistricting and changing the initiative petition process.

“I am calling on the General Assembly to take action on congressional redistricting and initiative petition reform to ensure our districts and Constitution truly put Missouri values first,” Kehoe wrote in a press release announcing the session.

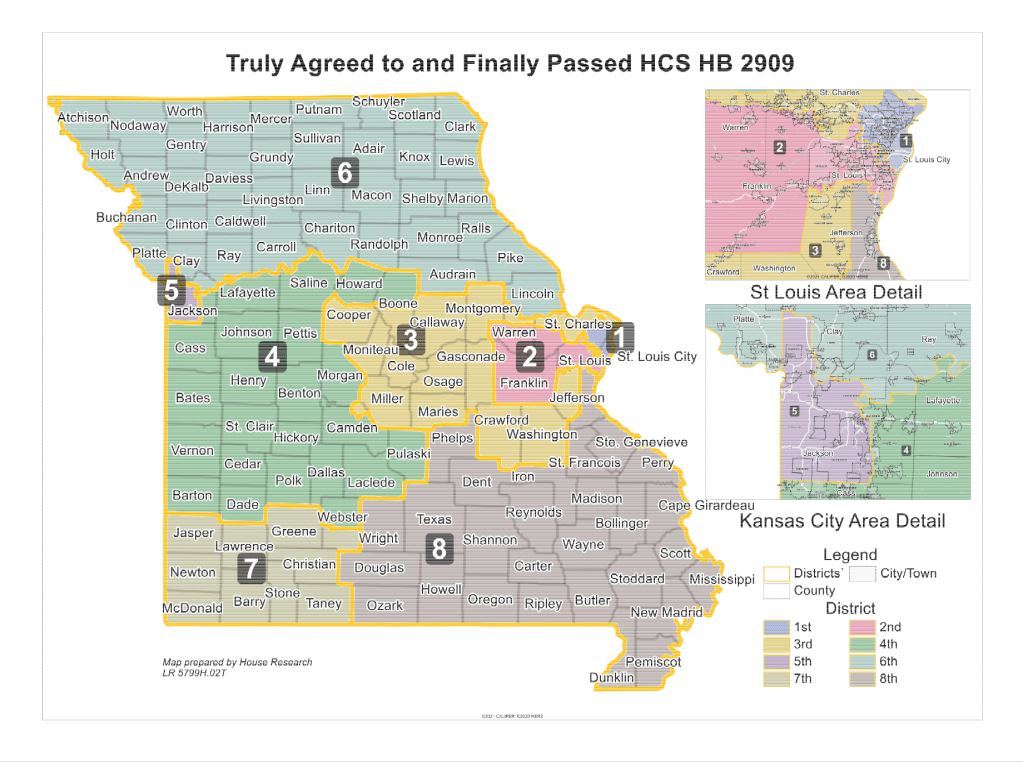

In the announcement, Kehoe unveiled his “Missouri FIRST Map” that would change the boundaries of six of the state’s eight congressional districts, including pulling much of Kansas City and Jackson County into a district that stretches to Jefferson City and northern Columbia. Read more here.

Missouri’s current congressional map gives no unfair advantage to either major political party.

That’s according to the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, which studies partisan redistricting and representation across the country.

The current map, drawn in 2022, includes six Republican-held seats and two Democrat-held seats and received an “A” from the project for its “partisan fairness.”

Takeaways

- Missouri’s current congressional map, which includes six Republican-held seats and two Democrat-held ones, is fair, according to a nonpartisan gerrymandering study.

- Under pressure from President Trump, Missouri lawmakers are now considering redrawing the map this year in hopes of replacing Rep. Emanuel Cleaver with a Republican in 2026.

- Some Republicans are concerned, however, that redrawing the map could spread Republican voters too thin and make safely red seats more competitive for Democrats.

- Democrats are vowing to do what they can to prevent a new map from being passed and are pushing for reforms to take redistricting power away from the state legislature.

But that might soon change as Republican state leaders, under pressure from the Trump administration, are now “likely” to call lawmakers back for a special session to redraw the map and split U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver’s district in Kansas City. Such a move would make Missouri another front in a larger gerrymandering “war” that has broken out across the country.

A ‘fair’ map

State lawmakers are constitutionally obligated to redraw the electoral map after every census. Missouri has had six Republican-held seats and two Democrat-held seats since 2011, when new census data caused the state to lose a congressional seat.

When the time came to redistrict after the 2020 census, conservative members of the Missouri Senate’s Freedom Caucus pushed for a 7-1 map that would change the boundaries of Cleaver’s district to make it more favorable for Republicans.

Others in the party weren’t convinced, raising concerns that gerrymandering Democratic voters from Kansas City into majority-Republican districts and pulling Republican voters into Cleaver’s district could make nearby seats less safe for Republicans.

The issue so divided the Republican majority that Senate leaders had to resort to arcane legislative tactics to get the map over the finish line before the end of the session.

According to a group of Princeton researchers, the current map is fair.

Comparing it to one million other possible maps, they found that a map with Democrats controlling one to three of the state’s eight total seats could be considered fair. As a result, the current map’s two Democratic seats earned it an “A” grade.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project also evaluated the overall competitiveness and geographic features of the map. The more compact the districts and the fewer split counties, the better.

Missouri’s congressional map earned an average score, or “C,” for both, with an average compactness score of 0.456 (just shy of the 0.5 needed to earn a “B”) and nine split counties. The state received an overall “A” score from the study, one of just 21 states to do so.

Missouri’s “A” grade makes it an outlier among its neighbors. Oklahoma and Arkansas received a “C” for partisan fairness, while Illinois, Tennessee and Kansas received an “F.”

According to the study, Kansas’ congressional map — also implemented in 2022 — gives Republicans a “significant” advantage, unlike in Missouri. Like Missouri, it received a “C” for competitiveness and compactness, but its overall grade remained an “F.”

State Sen. Maggie Nurrenbern, a Kansas City Democrat, was in the statehouse for the redistricting vote in 2022 but didn’t play much of a role in the process outside of voting on the map. She said the 6-2 split, while better than the 7-1 version, is still unfair.

“If we look at the breakdown in Missouri in terms of our electoral split, we really are a 60-40 state. That would mean having three Democrats in Congress,” Nurrenbern said.

A midcycle redistricting change

When President Donald Trump leaned on Texas Gov. Greg Abbott in July to redraw Texas’ congressional map, he started a domino effect of Republican and Democratic states alike considering rare redistricting in the middle of the census cycle to give their parties an advantage in the U.S. House ahead of the 2026 midterm elections.

The news that Missouri was on the president’s list was first broken by Punchbowl News, which reported that Republican U.S. Rep. Bob Onder of Lake St. Louis spoke with the president and later said the administration wanted Missouri to redraw its map.

Members of the administration later began calling Missouri lawmakers and Gov. Mike Kehoe directly to pressure them to redistrict, according to the Missouri Independent.

The president’s proposal was embraced by the Missouri Freedom Caucus, which released a statement calling on the governor to convene an extraordinary session to redraw the map “consistent with President Trump’s recommendation” and make changes to the initiative petition process.

“As conservatives, we cannot continue to allow the voice of Missouri’s voters to be diluted by judicial activism, well-funded left-wing ballot campaigns by out-of-state billionaires and weak congressional maps. The (caucus) is urging Governor Kehoe to stand strong for conservative values,” Missouri Freedom Caucus leader Nick Schroer, a Republican senator from Defiance, wrote in the statement.

Rep. Mark Sharp, a Democrat from Kansas City, said following the precedent of only redistricting after a census “would be the best way to uphold Missouri values.”

“If they want to make it a 7-1 map, then they have every right to do that after we take our census,” he said.

While the Freedom Caucus fully embraced the president’s plan, others Republicans were less eager about the idea, including Bowling Green Rep. Chad Perkins, the House speaker pro tem.

Perkins and others, including Lee’s Summit Republican Sen. Mike Cierpiot, have raised the same concerns as during the redistricting fight in 2022, arguing that gerrymandering the boundaries of Cleaver’s seat could make neighboring districts more competitive for Democrats.

“I don’t have any reason not to support a 7-1 map other than I want something that is sustainable if we have an off-year for Republicans like we did in 2008,” Cierpiot told The Beacon. “Every time I laid the results from 2008 over (the map), it looked like three of those seats could have been in jeopardy, and that’s what concerned me at the time.”

He said competitiveness is still a concern for him, but he’s open to seeing what any proposed maps might look like.

“I’ve been told that all of the congressional people — now, this is just rumors; I have no idea if it’s true — have signed off on it. They certainly know their districts better than I do, so if they’re happy, then I’ll probably be OK with it, too. But I haven’t seen any numbers yet,” he said.

Nurrenbern said that if Republicans redraw the map, she’s confident that Democrats will gain ground in the long run.

“In the short term, we could see Republicans rent a seat more or less for two years in Congress and have Republicans represent seven out of the eight congressional districts,” she said. “However, the joke’s on them. I do not think it will take long for the tides to turn. And soon we will have three congressional Democrats, because those districts are becoming much more competitive.”

Another Republican, Sen. Mike Moon of Ash Grove, previously supported drawing a 7-1 map. But he recently told the Missouri Independent he’s more skeptical because “we would not want the tables turned the other way.”

Sharp said his impression is that some Republicans in the statehouse “feel this could backfire.”

“Doing something this ultrapartisan could definitely put a bad spotlight — one could even argue another bad spotlight — on the Republican conference. That’s one way it could backfire,” he said. “A second way it could backfire is that this could really light a fire under a lot of Democrats to get out there and be supportive, particularly in 2026 for the next midterm election.”

“It’s a slippery slope, and this is going to encourage other Democratic states to do the same thing, and ultimately, we end up with a more divided country,” he added.

Missouri’s congressional map has not been redrawn halfway through a census period since the 1960s, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that districts had to have as close to the same number of residents as possible.

The almost-unprecedented nature of the current redistricting debate makes it all the more “frustrating,” according to Nurrenbern.

“The gerrymandering that happens today happens in red states and happens in blue states,” Nurrenbern said. “However, everybody agrees to play by the same rules at the beginning of the redistricting — the maps are created, and then you go another 10 years, look at your census numbers and redraw the map.”

“What’s not fair is deciding to change the rules halfway through the game because Trump is so unpopular that Republicans are afraid they’re going to lose the U.S. House in 2026 unless they cheat,” she added.

Cierpiot said he disagrees with the argument that states can only redistrict immediately after a census.

“Apparently, it’s OK to gerrymander the heck out of a state if you do it during the normal cycle. I can’t believe that clown in Illinois is making noise when you look at what Illinois has done,” Cierpiot said, referring to Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker.

“I don’t think anybody’s upset that we might do 7-1. They’re upset because we’re doing it out of the cycle, and I think that’s nuts,” Cierpiot added. “It’s our right to do that if we want to. I’ve read that we must do it after the census, but we can do it at any time, I would think.”

Nurrenbern acknowledged that many of her Republican colleagues had opposed the 7-1 map in 2022 out of concern for the safety of other Republican seats, but said that this time, “I do think it will pass.”

“If Trump is behind it, we see that Trump rules like a king, and Republicans today have shown over and over again that they have no spine and will not stand up to Trump. They will do whatever they’re told to,” she said.

Despite Republicans’ and Democrats’ concerns, the president’s plan has gained traction, with Senate President Pro Tem Cindy O’Laughlin, a Republican from Shelbina, telling a Columbia radio station that it is “likely” that Kehoe will call lawmakers back to Jefferson City to vote on a new map in the near future.

O’Laughlin declined an interview request from The Beacon but provided a statement clarifying that despite “speculation about a potential special session on redistricting … no decision has been made at this time.”

“That responsibility lies with Governor Kehoe, and I support him in whatever path he believes is best for the state. My priority is ensuring Missouri’s representation in Washington reflects the values of our conservative majority at home. As national Democrats continue to embrace extreme policies, we must remain vigilant and do what we can to keep socialists from gaining more control,” O’Laughlin wrote.

Sharp said he “really (is) hopeful that this is something that won’t happen, and we haven’t heard anything yet, so every day, I grow more optimistic about it not being called.”

Democrats vow to fight redistricting push

If Kehoe calls lawmakers back to Jefferson City to redraw the map, Democrats are “not going to do what Texas (Democrats) did,” Sharp said, referring to lawmakers leaving the state to deny a quorum and try to delay votes on Texas’ proposed congressional map.

“We’ll definitely be showing up and showing out and making a fuss,” Sharp added.

Nurrenbern agreed, saying she and her colleagues would “do everything possible” to stop a 7-1 map from passing.

But she also acknowledged that “here in Missouri, Republicans have a supermajority. They do not need us even to make quorum in the state House or in the state Senate. So there is only so much we can do.”

Nurrenbern said she expects to see “a robust movement to enshrine in our constitution a measure that would make district drawing much fairer and more representative of Missouri voters.”

She said she specifically hopes the state will switch to having a nonpartisan demographer draw districts, a change Missouri voters had approved in 2018 but then shot down in 2020.

Under that policy, referred to as “Clean Missouri,” districts would have to be drawn to maximize competitiveness, with as close to a 50-50 split of Democrats and Republicans as possible.

Sam Wang, a professor at Princeton University and the lead researcher for the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, said: “We diagnose, and then citizens have to decide what to do about it.”

“About half of the states have ways to counter gerrymandering — Missouri citizens tried a few years ago,” he said, referring to Clean Missouri. “One good thing about what’s happening in the news right now is that it’s good for citizens to see the kind of cheating that is happening in plain view so it’s front of mind and so everyone can decide what kind of democracy they want.”