Debbie Ferrell-Day worries most about who will take care of her 37-year-old son if something happens to her.

Takeaways

- A new federal law that narrowly passed Congress will cut $1 trillion from Medicaid and leave almost 12 million Americans without health coverage.

- People living with disabilities who rely on home-based care are expected to be hit especially hard.

- Organizations designed to help people with disabilities find coverage and navigate the complicated federal system are also losing funding, making the situation more difficult.

Ian Day has Down syndrome. He lives in an apartment with a roommate. He works part-time as a bus boy. And he’s a Special Olympics medalist.

But Ian can’t drive, so Ferrell-Day, 70, takes care of that. And without her help, he would have trouble navigating bureaucratic obstacles like the ones that will come with President Donald Trump’s new budget law.

“Even though we’ve done everything we can to plan for his future and make sure that he’s in a good place when we’re gone,” said Ferrell-Day of Gladstone, “I’m worried about him if something happens to me because I’m his main person. I don’t know what will happen.”

Now some of the basic safety-net services he relies on are at risk.

The budget reconciliation bill that Congress narrowly approved in early July will cut $1 trillion of federal spending from Medicaid over the next decade and add work requirements and more frequent eligibility checks for people who need Medicaid coverage and other safety-net programs like food stamps.

The new law is expected to cause 11.8 million people to lose health coverage over the next decade by trimming the number of benefit recipients and pushing more costs onto states.

Advocates fear that people living with disabilities may be among those most harmed by Trump’s overhaul of the country’s social safety net. And federally funded organizations established to help are also in line for steep budget cuts.

“There’s a very bright light at the end of the tunnel and it’s a train that is just about to run people over.”

Rocky Nichols, executive director of the Disability Rights Center of Kansas

Rocky Nichols, executive director of the Disability Rights Center of Kansas, one of those organizations, said it’s difficult to be optimistic about what’s ahead for the disability community.

“There’s a very bright light at the end of the tunnel,” he said, “and it’s a train that is just about to run people over. I can’t sugarcoat this. It’s horrible.”

Advocates expect cuts to optional services

MO HealthNet, Missouri’s Medicaid program, covers 36% of working-age adults with disabilities. KanCare, Kansas’ Medicaid program, covers 30% of working-age adults with disabilities.

Although some of the provisions in the new budget law won’t go into effect right away, including the work requirements, states are likely to begin making changes to prepare for the added costs they expect. And those could start anytime.

Medicaid is jointly funded by state and federal taxes, overseen by the federal government, but administered at the state level.

Parts of the program can’t be touched because they are legally required. Institutional care, for example, is considered an entitlement that must be covered, limiting where states can cut dollars.

In Missouri, finding ways to cut Medicaid spending may be even more challenging because coverage for the population of adults added under Medicaid expansion in 2021 is enshrined in the state’s constitution and can’t be eliminated without voter approval.

States have to fund care required under the law first, said Elise Aguilar of the American Network of Community Options and Resources, a national nonprofit. “What’s left over is going to see reductions,” she said.

And what’s left over are largely optional services, which states are allowed to offer under waivers obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the federal agency that oversees the program.

One of the biggest optional services in most states, including Missouri and Kansas, is home and community-based care, which lets people stay in their homes rather than having to move to a nursing home.

People with disabilities are among the most reliant on that service, which could include anything from nursing care to personal help to transportation.

Long waits for home care

Missouri and Kansas have not said how they plan to navigate the loss of federal Medicaid funding, but most disability advocates are bracing for them to cut back on those at-home services. And that will have devastating effects, they said.

“The individuals being served want to live their best lives,” said Erika Leonard, chief executive of Starling, a nonprofit trade association that represents community providers in Missouri. “They want to choose where they want to live. They want to choose where they work. They want to be safe, healthy and happy. The program that is in place to help them is a lifeline. Medicaid is a lifeline for people with developmental disabilities.”

Home-based services have been cut before, Aguilar said. After the Great Recession of 2007-09, Congress gave states extra funds to help support the added need for Medicaid. Once those funds were rolled back, Aguilar said, every state responded by cutting home and community-based services.

“We’re going to be in a similar place now,” Aguilar said, “where we’re going to see federal dollars rolled back, and states are going to have to look at those optional services.”

Kansas is still recovering after rolling back those services a decade ago, Nichols said. The state’s waiting list for people with intellectual and development disabilities to get home care was 3,169 in 2003. A decade later it had increased to more than 5,000.

“Last time, waiting lists skyrocketed and it took us over 10 years to dig ourselves out of those cuts,” Nichols said. “The difference is the cuts in this budget make those cuts look like child’s play.”

According to KFF, in 2024 the total number of people waiting for home care, including people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, seniors and other adults with physical disabilities, was more than 710,000 across the United States.

But the situation can only get worse under new federal cuts to Medicaid, Nichols said. At a minimum waiting lists will grow, he said. But states could also cut people out of services they are already receiving.

“The waiver is a contract between the state and the feds,” Nichols said. “But under this (reconciliation) bill the state can go back and rewrite their program to really reduce the services people can get. And those are the services that sustain people’s lives.”

Ultimately, the taxpayers could end up paying for more expensive institutional care, such as nursing home care, if home-based care isn’t covered.

“It’s not just penny-wise and pound-foolish,” Nichols said. “It’s just foolish, period.”

‘It will gut us’

In addition to cuts to care, organizations in each state, like the Disability Rights Center of Kansas, which receive federal funding to help people with disabilities navigate bureaucracy and find services, are also in line for steep cuts.

Trump has proposed cutting 62% of the funds that go toward those organizations. If Congress follows through with those cuts, Nichols said, it would be hard to carry on. All of his organization’s funding comes from the federal government.

“It will gut us,” he said. “We’re the ones who pick up the pieces from the Medicaid cuts. We’re the ones who will help people navigate the system … Our job will get a lot harder.”

Robert Honan, who oversees independent living services for The Whole Person, a Kansas City nonprofit that helps people with physical disabilities, said he’s hopeful that some of the threatened federal changes will be delayed, giving states and organizations like his more time to prepare.

But there’s little question, he said, that challenges lie ahead for agencies like his and for people living with disabilities, who need health care services even more than the general population.

“The delivery of health care will change significantly for people on Medicaid over the next five to 10 years, no doubt about it, in light of these significant cuts,” Honan said.

In all, 17 million people are expected to lose health coverage in coming years thanks to federal changes to Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act marketplace. That’s a lot to absorb in a country that has always struggled with health care access, he said.

“How are they going to get health care?” he said. “Medicaid is a lifeline for many, many millions of people.”

Ian Day relies on Medicaid for health care. He also gets Medicare, Social Security and food stamps through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. And he can’t afford to lose any of those benefits, Ferrell-Day said.

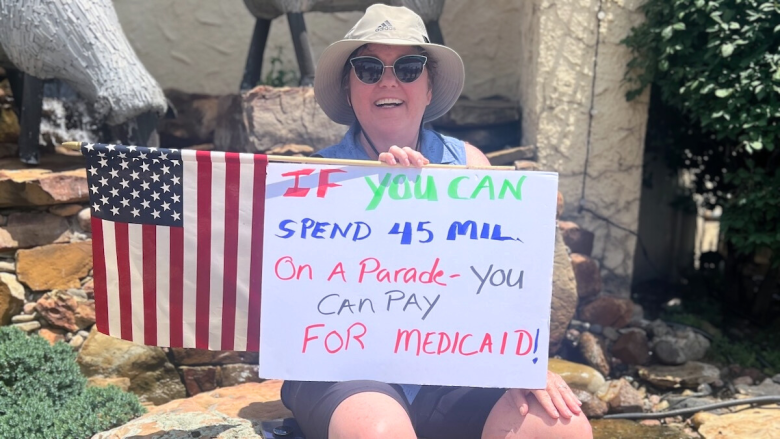

That’s why she calls her legislators on a regular basis. Visits their offices. And attends rallies and protests when she can. But she wasn’t surprised when the Trump-backed bill was adopted and signed into law July 4.

“I really felt like it would pass,” she said, “even with (Missouri U.S. Sen.) Josh Hawley making his comments about how he was fighting to keep Medicaid fully funded the way it is. But he voted for it anyway.”

In May, Hawley wrote in the New York Times that he and other Republicans “must ignore calls to cut Medicaid and start delivering on America’s promise for America’s working people.” He later voted for the Trump administration’s budget bill. But on July 15, Hawley introduced a new bill that would reverse some of the Medicaid cuts that could endanger rural hospitals.

If she does get a chance to talk to Hawley, Ferrell-Day said, she’d tell him about her son and people like him who really depend on Medicaid and the help it provides. She said Hawley voted against the best interest of his constituents.

“I don’t think it’s really going to hit them for a while just how important this … vote was,” she said.