On The Paseo near Admiral Boulevard, The Beehive’s doors are open for doctor visits and dental checkups.

Takeaways

- Late last year, the Kansas City Health Department issued a request for supplier qualifications for health care providers who treat the city’s poorest residents. Officials said they wanted to find out if millions of dollars from the city’s health levy were being spent appropriately.

- After objections from providers currently receiving health levy funds, the City Council paused the process. It is expected to restart soon.

- Some providers say they deserve a share of the taxpayer dollars, but there may not be enough to meet all the needs.

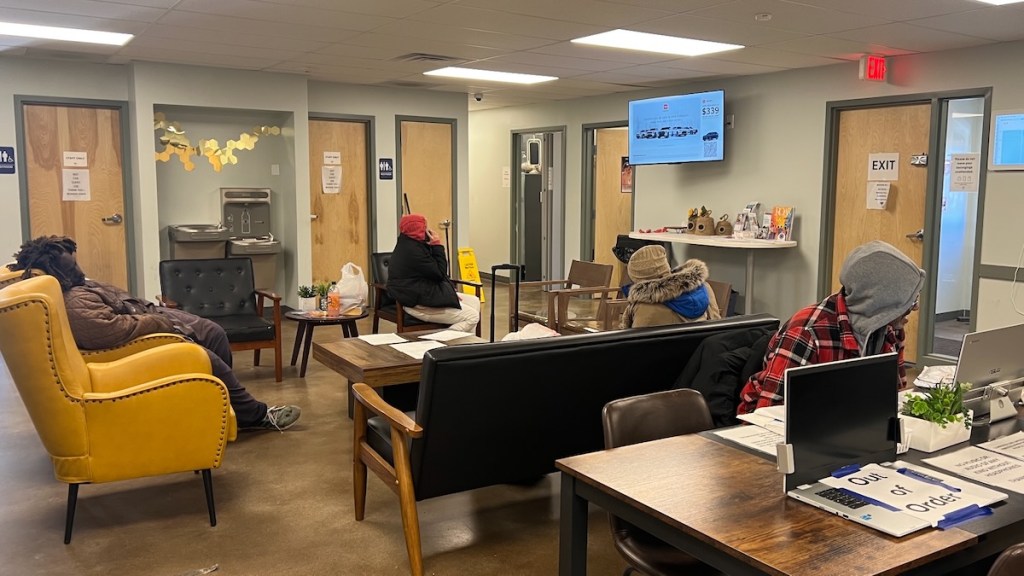

Care Beyond the Boulevard, which began a decade ago as a mobile health provider for Kansas City’s unhoused residents, has expanded to include this brick-and-mortar clinic where people can come for free health care and other services.

Between the care provided at The Beehive, its street medicine work and a new respite care facility not yet fully operational, Care Beyond the Boulevard served more than 3,400 patients through about 17,000 encounters in 2025.

“That’s not small potatoes,” said Jaynell “KK” Assmann, the organization’s founder and CEO. “That’s big.”

But not big enough to get Care Beyond the Boulevard a share of the Kansas City health levy, a property tax that brings in about $70 million annually.

The levy, which has been on Kansas City property tax bills since 1955, has long provided funding to an exclusive list of recipients.

In addition to the Kansas City Health Department, which is funded through the levy, the tax supports University Health — Kansas City’s safety-net hospital — and five other organizations: Children’s Mercy Hospital, Swope Health, Samuel U. Rodgers Health Center, KC Care Health Center and Northland Health Care Access.

Health providers that are not on that list, even if they care for the city’s poorest residents, get nothing from the health levy.

But that could change under a plan being pushed by the Kansas City Health Department.

For the first time in nearly four decades, the city is ready to undertake a review of health providers in order to understand which ones deserve a piece of health levy funding — and which may not.

The effort, launched late last year before being paused in January, has sent waves of uncertainty across the city’s health care landscape.

The city says it needs a better assessment of which Kansas City health providers are best equipped to meet the city’s health care needs.

But the providers currently receiving levy funds fear losing any amount of city support at a time federal and state funding are under serious threat.

And providers like Care Beyond the Boulevard that are on the outside of levy funding contend they already provide a substantial share of the city’s indigent care and should be let in.

There is something every side agrees on. The need is overwhelming. And likely to grow.

“I feel like we’re having the wrong conversation,” said Jeron Ravin, CEO of Swope Health. “We’re having a conversation about whether the health levy funding is fair. The real conversation is whether there are enough public health resources in Kansas City. And if the answer is no, how do we fix it?”

What has happened?

In November, the Kansas City Health Department issued a request for supplier qualifications, asking all safety-net providers currently receiving health levy funds and any others that wanted funding to make a case for their services and their plans for using taxpayer funds.

Care Beyond the Boulevard prepared a response to the request. So did Mattie Rhodes, Hope Family Care Center and Seton Center. They all said money from the health levy would help them expand services — including preventive health and dental care — to the vulnerable patient groups they already support.

“Even limited funding would allow us to sustain and expand access to care for communities that often have few alternatives for comprehensive, integrated services,” Ericka Saielli, CEO of Hope Family Care Center, wrote in a Jan. 8 letter to the City Council.

City officials said they had warned present levy recipients who currently receive a combined $34 million that a review would be coming. But once the request for qualification statements was posted, some of those providers raised strenuous objections.

They argued that the request had come too late in the budget year, leaving them little time to plan for possible reductions in city funding. And it came as they were facing a barrage of other cuts driven by the Trump administration.

Safety-net providers already are bracing for a drop in Medicaid coverage, revenue they are heavily reliant on. And they’re expecting to lose privately insured patients as well, thanks to the end to enhanced tax credits for insurance sold through the Affordable Care Act marketplace.

Meanwhile, Missouri Gov. Mike Kehoe has announced a budget proposal that would cut funding for community health workers and other patient outreach programs, which will affect community health clinics. And Kansas City Manager Mario Vasquez will propose a 2027 budget that includes a $2.8 million reduction in safety-net provider funding.

City officials said increased demands on the health levy fund due to lost federal funding and recent fund drawdowns for special projects, including a $9 million appropriation to Swope Health for the development of Swope Health Village, mean the city has fewer resources to share.

“To have city, state and federal funds all evaporating in front of our eyes,” said Bob Theis, Sam Rodgers’ CEO, “makes me very concerned about the safety net.”

But in a Jan. 8 memo to the City Council, Vasquez, along with Assistant City Manager Tammy Queen and Health Director Marvia Jones, said the request process was an effort to “ensure transparency, equity and compliance with procurement standards.”

“This initiative is not intended to dismantle the safety net system or redirect funds,” the memo said, “but to modernize oversight and confirm that public resources are used effectively and in alignment with voter-approved purposes.”

Requests on hold

Despite concerns about how levy funds are distributed, uproar from the providers currently getting levy funds prompted the City Council to pause the request for qualifications process, also known as RFQ, earlier this month.

In a unanimous vote Jan. 8, the council adopted a resolution to rescind the request. But the council signaled support for a future review, which is expected to begin with the Kansas City Health Commission in the next couple of months.

“I don’t necessarily see it as a bad thing to have people demonstrate the work that they’ve done in our community,” Councilmember Melissa Patterson Hazley said at the Jan. 8 meeting.

Sixth District Councilmember Johnathan Duncan, who serves on the health commission and introduced the resolution to pause the RFQ process, said he supports a review going forward.

“I’m not against moving toward an RFQ,” he said. “But there needs to be certain parameters of who is eligible to receive funds, what the impact will be on legacy safety-net providers who have received these funds and how this impacts our ability to provide care to our most vulnerable residents citywide.”

Kamera Meaney, University Health’s chief health policy and government relations officer, had a 60-page report ready to submit in response to the Health Department request before the City Council pushed pause.

The hospital, which has approximately 28,000 patient encounters each year that qualify for health levy funding, can not risk losing any of the city funding, Meaney said. That’s especially true in the current environment expected to bring greater patient needs.

“At the end of the day, everyone is worried about how we care for the patients,” Meaney said. “We have to find a way to care for these people because no one else is going to do it.”

Health levy history

That is why the Kansas City health levy came about in 1955, said Dr. Rex Archer, the city’s former health director.

The health levy was intended to support the public health department and help pay for indigent care at its city-owned hospitals, which became Truman Medical Center, an independent nonprofit now known as University Health.

The city later extended the scope and size of the levy to include other safety-net providers. But no specific providers are named in the original health levy, a maximum assessment of 50 cents per $100 in assessed valuation.

In 2005, about the time the Missouri legislature slashed Medicaid spending, putting financial strain on the city’s safety-net providers, city voters adopted a temporary extension of the health levy. That maximum assessment of 22 cents per $100 in assessed valuation did name University Health as a recipient.

In 2024, the actual assessment taxpayers were charged was 38 cents per $100 assessed valuation for the original levy and 17 cents for the temporary levy.

That temporary levy extension, which must be renewed every nine years, last came before voters in 2022, when 75% voted in favor. Ballot language specified that 15 cents of the levy go to University Health, while 3.5 cents goes to each ambulance service and “non-for-profit neighborhood health centers.”

About one-third of University Health’s levy funding comes through the temporary portion of the tax, meaning it is guaranteed. But the hospital is prepared to defend the dollars it gets through the permanent tax levy, Meaney said.

“We do understand this is taxpayer dollars,” she said. “We do understand that it is a privilege to receive it. And we do understand that we should be held accountable if we don’t use it appropriately.”

Over the years, the city has adjusted how much funding certain organizations were receiving and which organizations were getting funds, Archer said. And there has often been controversy and debate about which providers should be funded and whether they were using funds as intended.

In 2013, the city hired an accounting firm to conduct an audit of all the providers. And at one point, Archer said, the city began capping how much the levy would pay providers for each patient encounter.

“We’ve had such a swing in volume of these different providers in regards to how many patients they were actually seeing,” Archer said. “We really need to be watching that and looking at that every year.”

Health provider landscape

The city hasn’t conducted a thorough review for more than 35 years, according to the city manager’s office.

While current health levy providers are primarily in the city’s core, there is an unmet need in the city’s south, officials said. And organizations like Care Beyond the Boulevard and Mattie Rhodes are reaching patient populations that may not be comfortable going to traditional health clinics.

John Fierro, president and CEO at Mattie Rhodes, said his organization opened La Clinica, a one-day-a-week health clinic, two years ago after learning during the pandemic how many people needed affordable care that was “culturally competent.”

“They come to us for our ability to speak their language and to offer wraparound services,” Fierro said.

If his organization gets health levy funds, it will expand the services it offers and open up more days for appointments. Right now, La Clinica has a monthlong wait.

“Without any health levy dollars,” Fierro said, “we will continue one day a week and we have a model that allows us to break even. But … with the changes in health care in our country, there are a lot more people that are going to be needing health care, and in particular at a very affordable cost.”

Assmann said Care Beyond the Boulevard would use health levy dollars to continue meeting people where they are — including in homeless encampments and on the streets.

“We know for a fact that the patient population that we serve is not getting served anywhere else,” she said.

The organization is also restoring a motel at 5100 Linwood Blvd. for a low-barrier shelter with $7 million in federal funding allocated through the city. It is expected to have 26 medical respite beds and 13 other beds.

Who is getting care and how much does it cost?

Another reason for the request for qualification statements, the city manager’s Jan. 8 memo to the City Council said, was concern about data from current health levy providers that “show discrepancies between reported and verified patient care figures.”

The city’s contracts with the providers specify that health levy funding can only be used for Kansas City residents who have income below a certain level, for example, and who don’t have any type of health insurance.

When providers bill the health levy for patient encounters, they must provide documentation to prove the patient meets those qualifications. But the city said some safety-net providers have failed to adequately verify patient information, making it appear that the cost per patient encounter far exceeds the contracted rate of $147.

City-verified Kansas City resident patient visits in 2025

| Agency | # of annual encounters | # of unique individuals served annually | Annual cost per encounter | Total allocated funds (FY 2024-25) |

| Swope | 379 | 379 | $4,708 | $1,784,167 |

| KC Care | 2,067 | 727 | $274 | $565,916 |

| Samuel U. Rodgers | 4,604 | 2,171 | $212 | $973,978 |

| NHCA | 609 | 408 | $573 | $348,692 |

Source: Kansas City manager

Last year, according to city-verified numbers, Swope Health only had 379 encounters. The low count resulted in a per-encounter charge for the organization of more than $4,700.

Ravin strenuously objected to the city’s numbers, saying the health center treated many more qualified residents. But its staff can’t always verify residency for unhoused patients it treats.

He also argued that the health center’s staff has more pressing priorities when treating patients than tracking down patient IDs or utility bills. The city will also accept a signed affidavit and gives providers a year to file the paperwork.

But the requirements are still burdensome, Ravin said.

“We have some process things internally to take care of,” he said. “But what I will tell you is it feels like the intent to ensure that dollars are being used and spent appropriately has kind of turned into an endless barrage of regulatory barriers that are really more frustrating for providers than they are productive.”